Today, sadly, is the 25th anniversary of the start of neo-nazi David Copeland’s campaign of nail bomb terror in London. In an edited extract from his forthcoming autobiography, Gerry Gable reflects back on the events, the man behind the bombs, and the men behind him…

David Copeland

On 17 April 1999, a Saturday afternoon, a nail bomb tore through a busy market area in the centre of Brixton, south London. It was to herald the start of a deadly neo-Nazi terror campaign, and a desperate hunt for those responsible in which Searchlight was to play an important part.

The bomb was a crude device, a length of pipe packed with flash powder from large fireworks, with a detonator and a timing device made from a modified alarm clock, all packed into a box in a sports bag with about 3 kilos of nails poured in and around it for good measure. It was left outside the Iceland supermarket near Brixton tube station but had been moved around the corner by a market worker and left on top of a dumpster. That helped to reduce the casualties. Had it exploded in the crowded street, as was obviously intended, the casualties would likely have been more numerous and more severe. As it was, there were many injuries, some of them very serious, but no-one was killed. One photo became a lasting image of the attack: an X ray of the head of a two-year-old girl in which was embedded a three-inch nail

It was clear to us that this was a racist attack. And, although the device was crude, it represented a considerable step up in the intentions of at least some elements of the extreme right.

At that time, we had an infiltrator, codenamed Arthur, working inside the BNP and other far right groups. From him we knew that, initially, there was as much bewilderment and speculation in the BNP about who was behind it as there was on our side of the fence. The obvious candidates were Combat 18, but we had so seriously penetrated that group that we would have known if anything like this was planned. And we knew they were beginning to panic that it might be blamed on them anyway. Arthur made himself very busy, or as busy as he could without attracting suspicion, but he heard nothing indicating who might have been behind the attack.

A week later, there was another bomb, this time in the Bangladeshi area of Brick Lane in east London. Again, had things gone as the bomber intended it would have been far, far worse. The target was Brick Lane market, but the bomber did not realise it only took place on Sunday, not on Saturday. So, he dumped the bomb between two parked vans in Hanbury St, a little side turning off Brick Lane where it was found by a local man. He thought it had been lost and took it to Brick Lane police station. When he found it closed he dropped the bag into the boot of his car where, shortly afterwards, it exploded.

Arthur was becoming very frustrated; what was the point of what he was doing if we were helpless in finding out who was behind this? But he kept at it, phoning around people in the far right, looking for just the smallest clue.

The breakthrough came when police spotted, on CCTV footage, someone carrying the sports bag in which the Brixton bomb had been housed. The picture was very poor quality, so the Met sent it to NASA in the US for special enhancement. The image which emerged was soon on the front pages of the papers, and when Arthur saw it in the newspaper rack of a local shop it electrified him. He stared at it. “I know him!”

At home he immediately turned on the TV and watched the news reports. He saw the image coming up time and again and the more he saw it, the more convinced he became. “I think it’s Dave…” The young man he thought he recognised was 22-year-old David Copeland, who had joined the BNP two years earlier. He turned up at numerous BNP events but was always a bit of a loner, a bit apart. Arthur had spoken with him a few times and occasionally they had chatted over a pint, but Copeland was not someone that Arthur, or anyone in the BNP for that matter, knew particularly well. Nevertheless, his name was recorded in Arthur’s reports of those meetings.

Copeland harboured deep and profound hatreds: he despised black people with a passion and was driven by a bitter antipathy towards gay people, almost certainly the result of being teased when younger about possibly being gay himself. In 1999, he was working on the Jubilee Line extension in Bermondsey where his father had got him a job. He couldn’t even find work by himself.

At one BNP meeting, at the Swan in Stratford in September 1997, Copeland was pictured standing next to a bloodied John Tyndall during a confrontation with anti-fascists. (We later learned that Tyndall had merely fallen over during the melee and banged his head on the pavement).

But nursing the hatreds that he did, the BNP could not satisfy Copeland’s lust to take the war to his enemies. He read the Turner Diaries, that vile American blueprint for race war and genocide. He began to cast around for options more militant and extreme than the BNP could offer. Then, by chance, he heard about the National Socialist Movement, the creation of a long standing British nazi, Dave Myatt.

Myatt began a long political odyssey in the late 1960s when he joined Colin Jordan’s original National Socialist Movement. From there he moved to British Movement. Despite a purported “search for truth” that has taken him to Christianity, Buddhism, radical Islam and Satanism, the national socialist component of his philosophy has never waned.

Myatt’s philosophy centres around the idea that individuals should seek to overcome their limitations and embrace their inner darkness in order to achieve a higher state of being. This philosophy would later form the basis of the Order of Nine Angles, a bizarre satanic-nazi cult founded by Myatt using the pseudonym Anton Long, which advocated the most extreme forms of personal behaviour – including sexual behaviour – to purge devotees of the moral limitations imposed upon them by the ‘ZOG-controlled’ state and enable them to do what was necessary to ensure the victory of the white race. This sect was, in later years, to crop up in connection with nazi terrorist cases in Britain and the United States, resulting in arrests and convictions.

Arthur had been to an early NSM meeting in Chelmsford in November 1997. It was opened by Steve Sargent, brother of C18 leader Charlie Sargent, whose main concern seemed to be absolving Charlie of the accusation that he was a police informant.

Steve Sergant

The more interesting speaker was a young man called Tony Williams. Arthur’s report notes that Williams attacked the BNP for calling the NSM “Hollywood nazis” and declared that he believed the NSM could form a government. And then he started attacking the Jews.

Dave Myatt spoke last and told the 20-odd people present not to be disappointed by the low attendance because they represented “the cream of Great Britain” and would ultimately prevail.

Myatt had authored a call for terrorist action called “System Breakdown – A Guide to Disrupting the System” setting out a design for a terrorist campaign along the lines of that in the Turner Diaries. He also wrote an essay entitled A Practical Guide to Aryan Revolution, posted online in November 1997. It advocated violent race war and included chapters on “Assassination” and “Terror Bombing”.

Race war, it argued, “… means creating tension and terror within ethnic communities and damaging their homes by firebombs and explosive devices. Part of this involves attacking individuals (and killing some of them)”.

David Copeland joined the NSM in early 1999 and only a few weeks later, now living in Fleet, in Hampshire, was appointed NSM Southern Regional Organiser. A letter from Tony Willams welcomed him into “leadership, responsibility and accountability to your comrades”. He obtained a copy of Myatt’s “Practical Guide to Aryan Revolution”, studied it and absorbed it. From other NSM literature he got hold of the web address which provided him with instructions for making a bomb. Now, the nail bomber was primed.

Shortly after we gave the police Copeland’s name, and an address we had for him in Barking, the police received information from one of Copeland’s Jubilee Line workmates who provided his name, but also, crucially, his phone number, which was listed to the house in Fleet where he was now living.

However, although the CCTV image had led to Copeland being identified, and establishing that he had extreme right connections, as far as the police were concerned it only had the effect of moving him up the list of names they were methodically working through.

But it spooked Copeland. He saw it on the front page of the Evening Standard as he came out of a porn shop on Soho. He immediately went home, collected a bomb he had has just finished making, returned to London and hid out in a cheap hotel in Victoria. He had originally planned to plant the device on Saturday, as with the earlier devices, but now he could not wait. The next day, Friday 30 April, he took it to the Admiral Duncan, a gay pub in Soho, and left it. It was the most devastating of the three attacks: three people died, three friends: Andrea Dykes, who was 4 months pregnant, Nik Moore and Jon Light. Andrea’s husband was seriously hurt. They had met up to celebrate her pregnancy. 79 others were injured, many seriously and some having to have limbs amputated.

Copeland went back to Fleet where later that evening he was arrested. Even now he was not being treated as a target suspect; the two Flying Squad officers who turned up at his address were amongst those still routinely working their way through a list of possible names on which Copeland was number 10. Only when they went into his room and found it decorated like a nazi shrine, with bomb making equipment scattered round and a partially made bomb under the bed, did it become apparent that David Copeland was more than just another name on a list.

Searchlight’s information about Copeland was passed to the Met’s Special Branch five hours before the Admiral Duncan bomb exploded. It would always have been too late to prevent it, given that Copeland was, at that time, out and about in London. That is, to us, a lasting source of regret. But even so, Copeland had already been arrested by the time SB shared it with the investigation team; when Flying Squad officers turned up at Copeland’s home, it still had not been passed over.

When Copeland came to trial, the police and the prosecution were peddling hard the notion that he was a ‘lone wolf’, acting out of his own deranged motives. And, lazily, most of the press coverage followed that narrative.

The exception was the BBC’s Panorama programme, which was made by Andy Bell, then the programme’s Specials Producer, and Nick Lowles, who was seconded from Searchlight as Assistant Producer. The reporter was veteran crime journalist Graeme McLagan. Virtually alone they investigated the links between Copeland and the NSM and the extent to which he had been influenced by Myatt, Tony Williams and the like. The programme, broadcast immediately after the trial ended with Copeland’s conviction, documented those links and analysed what had happened. By 1999, it said:

“…a fatal chemistry was taking place. Copeland, the loner, deeply insecure about his sexuality and nursing a loathing of black people and gays, was feeding on a diet of literature which developed and sharpened his hatred and his anger.

From the Turner Diaries he absorbed the idea of sparking a campaign of terror against the enemies of his race.

That idea was fuelled by the writings of the NSM whose literature also provided the internet website address from which Copeland got his instructions in bomb making.”

With intelligence from Searchlight, Panorama then set out to track down and confront the NSM leaders who had had such an evil influence on the young, inadequate David Copeland.

Williams hides from Panorama

They had no real success putting questions to Williams: he was holed up, in his converted vicarage in Norfolk, and despite some ingenious ruses to get him to show himself, he could not be drawn out into the open.

Steve Sargent, at this time, was being equally shy, surfacing just once a day and driving from the council estate in north London where he lived to a local park to exercise his pit bull terrier. He was accosted by the film crew as he drove out of the estate car park. The exit was blocked off with a van and he was questioned through the window of the car by Graeme McLagan. Not surprisingly, he said nothing and kept his head very low. When it was judged enough time had passed that the viewer would be able to form a view as to his reactions, the vans were withdrawn, and he was allowed to leave.

Steve Sargent confronted by Panorama

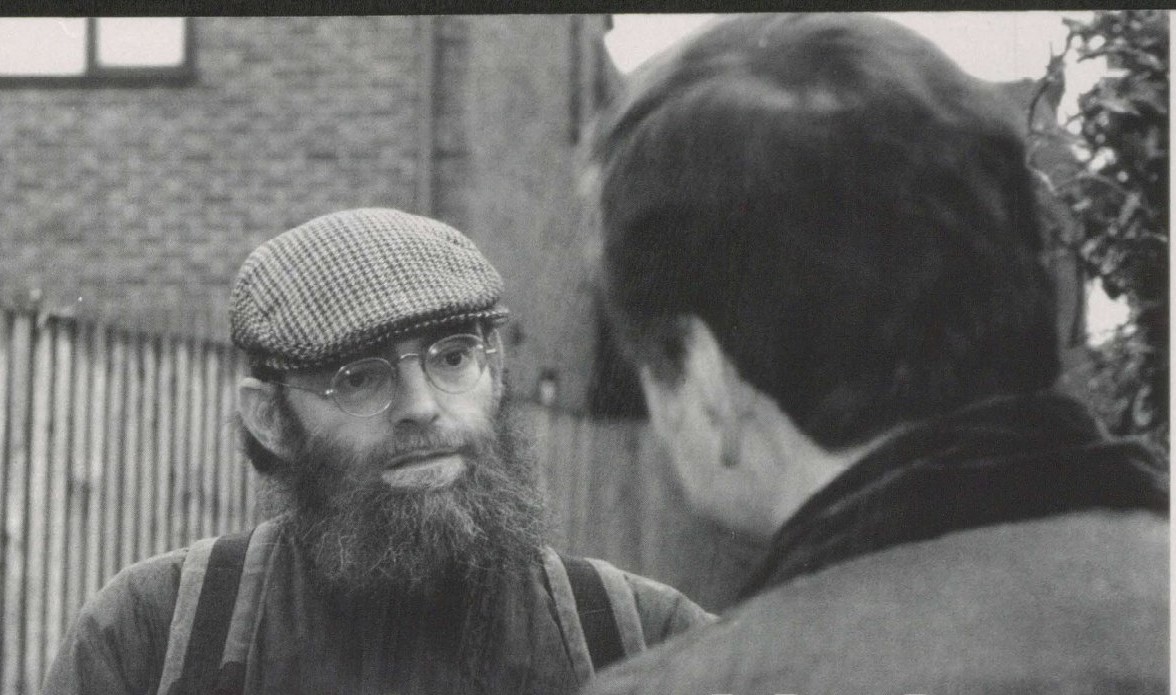

The third doorstep was by far the most telling. David Myatt, living in rural Cambridgeshire, was being watched by an ex-police surveillance officer with a specially-kitted out van. His movements were established and when, in the morning, he cycled through a narrow passageway from his quiet street to the nearby main road, Myatt’s route was blocked by Panorama’s film crew. Again, his retreat was sealed off by a parked van, and he was interrogated by Graeme McLagan.

Repeating that he had no comment to make, even when provided with the opportunity to deny any influence on Copeland, Myatt only broke from his script once, when McLagan asked him “Any guilt?”

“What I feel” he replied, “is between me and God. It is nothing to be made public. It is a private matter”.

He might try telling that to the bereaved and maimed and injured victims of Copeland’s attacks.

Copeland entered pleas of manslaughter on grounds of diminished responsibility. He was nevertheless convicted of three counts of murder and other offences and sentenced to serve at least 50 years in prison.

I was interviewed for the programme and the producers gave me the last word. I said:

“You have to look at a young man like Copeland and think here is a young guy who’s done terrible damage to our society, he’s killed, he’s done terrible damage to himself and his family as well. Who, at point A, is responsible for all of this? Who woke those terrible ideas up in that boy’s mind?

“I think you just go and see who produces this hate material, and you know…”

You can watch the Panorama investigation here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vhf-NwlIVtc

David Copeland is guaranteed a warm welcome in UKIP.

UKIP seems to draw its inspiration and leadership from convicted crooks like Rogue Builder Chairman Permanut National Ben Walker (expelled JP), fraudster Dan Morgan and the charming but expelled by voters and banned from public office for three years Pembrokeshire ex-Councillor Paul Dowson with an arm-long list of convictions for a bewildering range of offences including several for drugs, etc.

The same Ben Walker, who lied and lied again in his outrageous application to become a magistrate, proudly declared at its bent leadership hustings on the evening of Tuesday April 16 — surely everyone knows it’s a shooo-in for the Viagra’d-up, Golliwog-brandishing obese oaf — probably doesn’t get many opportunities to embrace decent people.”We don’t care if anyone’s got a past or a black spot, we embrace that, because we’re human”. When decent people wouldn’t touch Walker with a cattleprod unless it was all charged-up, he has little choice but to embrace only fellow rogues like the Dudley Duffer. Oh the tales from there!

So while UKIP may recruit is Top Cadre from outside Belmarsh and Broadmoor, it may have to wait for another 25 years to get its mitts on Copeland.