Mussolini’s ‘proud boys’

A century ago, Italian fascists set up the first offshoot of the Fasci di Combattimento in London. Alfio Bernabei reflects on the genesis of the movement in the UK

The fascist “league of combat” was formed in Britain 100 years ago, in the spring of 1921. It was the work of Italians – Mussolini’s London-based “proud boys” – who were military men with a mix of business and academic backgrounds. The league was set up as an offshoot of the Fasci di Combattimento (later the National Fascist Party (NFP)), which had been launched in Milan by Benito Mussolini in March 1919.

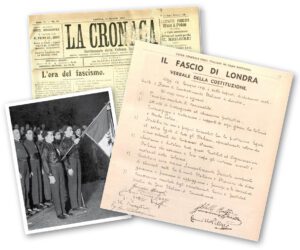

The London branch was the first inroad of Blackshirts outside of Italian borders. The exact date of birth of the London fascio – 12 June 1921 – appears in a handwritten document, about the size of A4, headed “Il fascio di Londra – Verbale della Costituzione” (The fascio of London – Report of its constitution) (see facing page). The heading, in black ink and bold characters, indicates that the “combatants” took the trouble to order it from a printing shop before they met for the signatures, which takes the date of the actual discussions and preparations surrounding the formal launch of the league probably back to May, or even earlier.

The handwritten text begins: “Today, 12 June 1921, the undersigned declare that the Fascio di Combattimento Italiano a Londra (The Italian Fascio of Combat in London) has been formed.”

The document lists seven aims. The first recommends “upholding absolutely the principle of nationality and the launching of propaganda activities and patriotic education”. Then comes a set of measures aimed at putting under strict control the Italian community in the UK, about 20,000 people at the time. (This aim, by the way, was fully implemented.) The penultimate article envisages the setting up of an organisation of “fascist sympathisers chosen among Italian and foreign like minded people” (foreign “minds” in the original).

The recruitment of “foreign minds” went hand in hand with the idea that, as a doctrine, fascism had universal appeal and could expand in the same way that the Catholic Church had successfully done for centuries. Mussolini was following this example in hailing the “universal spirit” of fascism. This vacuous definition can be easily ridiculed but, as we can see at the present time, behind it lurks a continuous threat with concrete possibilities of soft or violent resurgence.

The document was signed by eight men, including some who in the following years helped to successfully subjugate the Italian community in the UK with fascist party branches established in more than a dozen towns – from Cardiff and London to Edinburgh and Belfast.

The first signatory on the list is Giuseppe Moraschi. He was an army captain who five months later helped to organise the first march of Italian Blackshirts to Westminster Abbey (the first march planned in 1921 was cancelled at the last minute at the request of the Home Office; it was to take place in full fascist uniform in 1922).

Fourth on the list was Giovanni Savani, editor of the Italian newspaper in London, La Cronaca, that in 1922 turned into the fascist weekly, L’Eco d’Italia. Its offices were at 14 Little Howland Street, Soho. Other signatories were Camillo Pellizzi, a professor at University College London who was in personal contact with Mussolini, and Achille Bettini, who was to become secretary of the NFP in the UK.

Beginnings

The seed of the Italian Fascio of Combat in London had been planted two years earlier, on 4 November 1919, with the setting up of the Unione Reduci Militari Italiani – Sezione di Londra (URMI), an association of Italian ex-soldiers from the First World War. One of its most prominent members was Antonio Cippico, another professor at University College London. According to a report published later by the NFP in the UK, it was at Cippico’s house near Holland Park that the creation of the London Fascio of Combat was discussed.

With the founders comprising army people and intellectuals, it certainly wasn’t the concept of poorly educated hotheads. Both Cippico and Pellizzi also wrote for the newspaper that Mussolini edited at the time, Il Popolo d’Italia. Significantly, the most prominent advertisers in the Italian fascist newspaper in London, L’Eco d’Italia, were two Italian banks with some British directors and the Pirelli tyre company.

Relatively few people in the spring of 1921, in Britain, were aware of fascism and Mussolini. The March on Rome, the mass demonstration that led to Mussolini and his party taking over the government, was still more than a year away. Probably better informed would have been the readers of The Daily Herald, edited by Labour MP George Lansbury, and those of Workers’ Dreadnought, edited by socialist and suffragist Sylvia Pankhurst. She had got to know the Italian anarcho-syndicalist Silvio Corio, who had contributed to the newspaper while being a member of the group of Italian political exiles active in and around Soho. This was the group that in 1922 created the first organised antifascist movement outside of Italy.

Questions remain to what extent the creation of the Fascio of Combat in London encouraged British sympathisers to develop their own variant. Most historians have left an unexplored two-year gap between 1921 and 1923 when the “British Fascisti” was set up by Miss Rotha Beryl Lintorn-Orman, following the publication of an advertisement seeking like-minded anti-communists in the right-wing journal The Patriot in February 1922.

Historian Steven Woodbridge, in a recent essay, stressed the importance of looking into this early period to fully understand the impact of Italian fascism in the genesis of fascism in Britain, before historians jump to Oswald Mosley’s creation of the British Union of Fascists in 1932.

Lintorn Orman herself came from a military-intellectual background close to that of the Italians behind URMI and the Fascio of Combat; there may have been contacts between them long before they appear to have shared an address in Great Russell Street in London. There is evidence of a fascist Anglo-Italian line of communication as early as 1921 via a former army officer and writer, Harold Goad, who consorted with the Italian Blackshirts.

Some British sympathisers were on good terms with the fascio long before they attended the first Italian Black Shirt Gala Ball at the Cecil Hotel in February 1923. The role of Sir Rennell Rodd, the former British ambassador to Rome and a fascist sympathiser, needs to be fully explored alongside that of the British-Italian League of which he was a member.

Woodbridge is right in urging a reassessment of historiography regarding the genesis of fascism in Britain and the influence of Italian fascism in its development. After examining the role of the so-called British radical right or die-hard right within the Conservative Party, he writes: “In truth, British fascists at this time were not just ‘dreamers’ or paying mere lip-service to Fascism. They were determined to put their fascist doctrine into practice, despite the sometimes violent or illegal consequences.”

A number of episodes between the creation of the Italian Fascio of Combat in 1921 and that of the British Fascisti remain unexplored. These range from the adulatory articles in the British press about Mussolini, treated as an ideal leader even before the march on Rome, to the decision by the British Embassy in Rome to allow NFP secretary Michele Bianchi, who was an expert in the elimination of trade unionists, to enter its premises for talks – again before that fateful march. There also appears to have been some sort of agreement between Mussolini and Scotland Yard in 1923, apparently aimed at monitoring the activities of Italian anti-fascists in London.

So, by the time Mosley came onto the scene in the 1930s, supported financially by Mussolini, the terrain for fascists had been well prepared.

An essay by Alfio Bernabei on the same subject, alongside another by Steven Woodbridge, appears in the book Fascism and Anti-fascism in Great Britain, published in English by Pacini Editore, Italy, 2020

Caption:

Handwritten constitution of the Fascio di Londra; an early edition of the fascist La Cronaca; and London Blackshirts welcome Mussolini at Victoria station in 1922 months after he took over government