BOLOGNA’S FIFTH MAN

By Alfio Bernabei Published in Searchlight in Summer 2021

They call him “the fifth man”. Paolo Bellini, a self-confessed killer and former member of Avanguardia Nazionale, a fascist organisation with links to a branch of the Italian secret service, is currently on trial accused of playing a part in the 1980 Bologna bombing at the railway station. Among the 85 killed two were Britons – Catherine Mitchell and John Kolpinski.

In the course of investigations and several trials during the past 40 years, four people have so far been found guilty and given prison sentences. They are Francesca Mambro, Valerio Fioravanti, Luigi Ciavardini and Gilberto Cavallini.

In January this year, in explaining the life term given to Cavallini, the judges reiterated that it was wrong to think that the bombing was carried out by a gang of four acting alone. Cavallini was a former member of another fascist organisation, Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari (NAR). The judges stated: “It was a political massacre, or more accurately, a State (sanctioned) massacre.”

As well as the four perpetrators they named the masterminders and architects behind the atrocity and the sidetracking strategy planned months in advance – Licio Gelli, Umberto Ortolani, Federico Umberto D’Amato and Mario Tedeschi, now all dead.

Gelli, head of the Masonic Lodge Propaganda Due (P2) and Ortolani provided the money from Swiss bank accounts to pay the fascist criminals. D’Amato, who had links with NATO, the Stay-Behind/Gladio organisation and led the Office for Reserved Affairs of the Ministry of the Interior deployed secret agents involved in the planning and cover-up. Tedeschi, a magazine editor, was one of those in charge of influencing media coverage to send investigators off track.

The political motivation behind this and other terrorist attacks during the so-called Years of Lead”(designating a period of social and political turmoil) was to keep Italy within the Western sphere of influence by preventing the Communist Party, the stronger in Western Europe at the time, to gain power. The Bologna massacre was designed to sow confusion and keep the Army on the alert, and the whole population, political establishment and the press were made to feel under vigilance.

And Bellini? What part was he playing in all this, and why is he now at the centre of a new trial accused of being the “the fifth man”?

Bellini was born 68 years ago in Reggio Emilia, a town in central Italy, 45 miles from Bologna. The town has a long-standing reputation of radical left-wing politics and embodiment of what was known as the “red belt”. Bellini’s father had rightwing sympathies and his son followed his example by joining Avanguardia Nazionale, the fascist organisation set up in April 1960, more extreme than the post-fascist Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI). It was headed by Stefano Delle Chiaie, the fascist militant leader who in 1970 was accused of taking part in the attempted coup d’état known as “golpe Borghese”.

One of the first people killed by Bellini on orders from Avanguardia Nazionale was Alceste Campanile, a young man from the same town who belonged to the leftwing organisation Lotta Continua. He was shot dead in cold blood in a country road in 1975. Although Bellini wasn’t identified as the killer (he admitted responsibility only in 1999), he fled Italy to Brazil. This was the time of Operation Condor when a number of European nazi-fascist militants in trouble with the authorities found it easy to take refuge in Latin America.

After acquiring false papers Bellini returned to Italy with a new identity. Under that name, Roberto da Silva, he was arrested in 1981 for the theft of antique furniture, together with Agostino Vallorani who had links with the London scene of art dealers and a large group of Italian fascist fugitives from justice.

In prison, he was reidentified as Bellini. Once released, he gained a Light Aircraft Pilot Licence, while pursuing shady activities in the illegal trade of works of art. At some point he came into contact with Mafia bosses.

In the early 1990s, after a theft of paintings from a mseum in Modena, the carabinieri police assigned to track down stolen works of art asked for Bellini’s help in finding out whether the Mafia was responsible. In Sicily, he became enmeshed in Mafia plans to blackmail the State – either five top Mafiosi in jail would receive privileged treatment or works of art and ancient buildings, such as the Leaning Tower of would be destroyed.

Bellini was playing a double game. On the one hand he was an active criminal, a killer of apparently up to ten people, on the other, he was passing information to the authorities to keep up his role as a collaborator with justice in order to stay out of jail. Unsurprisingly, in a recent book written about him by Giovanni Vignali there are more questions than answers.

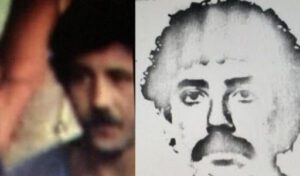

When it comes to the massacre in Bologna in 1980, in early investigations two witnesses claimed that Bellini had been in town that day. But he produced evidence deemed credible enough to save him from further enquiries. The reason he has become a major character in the current trial is because film footage has come to light that, like so many documents had remained unnoticed or been deliberately kept out of sight.

The footage was shot by German tourist who had passed through Bologna railway station shortly before the explosion. It shows the clock and one of the frames captures a face resembling Bellini’s. Although he continues to deny his presence at the station, Bellini’s former wife says that it is definitely him. The alibi he presented in coming under scrutiny.

More, and equally disturbing, findings have emerged that make this trial so important. When the bombing took place, the chief magistrate in Bologna with the duty to guide the investigations was Ugo Sisti but he suddenly disappeared from town. No one could find him. It has now been established that he went to stay at a hotel ran by Bellini’s father. A strange coincidence.

Back in Bologna, Sisti seemed to support rumours that attempted to explain the explosion as some technical fault rather than a terrorist attack. Simultaneously, an agent of military intelligence and member of P2, Pietro Musumeci, turned up in Bologna putting himself virtually in charge of the investigations. More revelations have emerged according to which Bellini apparently piloted a small plane to Rome that took Sisti to see the then Interior Minister.

And there is something perhaps even more startling. Apart from Bellini, another witness whose activities are puzzling has been called at this new trial. He is Domenico Catracchia, formerly an administrator of a company that looked after flats in Via Gradoli in Rome, a street associated with offices used by the secret service.

In the 1970s flats were apparently made available to members of Avanguardia Nazionale, the fascist organisation to which Bellini belonged, and to certain members of the Red Brigades. Coincidentally, Via Gradoli is the street where the former politician Aldo Moro was kept prisoner for a time after his kidnapping by the Red Brigades in 1978. He was killed after 55 day in captivity.

Catracchia is accused of providing false information. The Judges will probably want to know to what extent he was aware that the secret service may have shared premises with fascist organisations like Avanguardia Nazionale and NAR (the latter implicated in the bombing) with the potential evidence supporting their view that it was not the spontaneous act of four or five fascists but a state-sanctioned massacre.

Bellini insists that he wants to be a state witness, but it remains to be seen if he will tell the truth or, as always, be selective with the information in his possession? The families of the 85 victims of the atrocity still demand justice. As one of them put it: “Part of the truth is never the truth.”