Alfio Bernabei reports on the commemoration of an event addressed 100 years ago by suffrage campaigner and socialist Sylvia Pankhurst, who was one of the first to warn the world outside Italy of the dangers of fascism – a warning that still holds today

First published in the Spring 2023 issue of Searchlight magazine

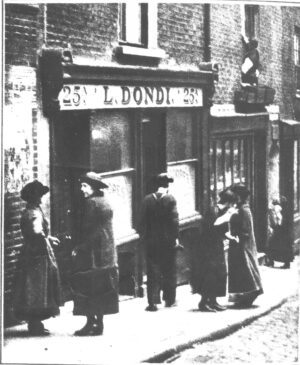

Dondi’s Club as it was 100 years ago

The re-enactment of historical events nearly always prompts feelings of participation and reflection. Those taking part are usually prepared to set their mind on a path between past and present, with a sense of wanting to embrace the significance of the recollection and give it continuity in time.

This was certainly the case for the event that took place in March this year in a quaint three-storey building in Clerkenwell, a part of London once known as Little Italy. The venue was packed and the audience was enraptured as the story unfolded. There was something in the air – as if the walls had ears, or retained echoes of voices which gave warnings that went unheeded, a failure for which humanity paid a heavy price.

The event was staged to mark the 100th anniversary of the meeting against fascism in Italy that took place at Dondi’s club on 25 March 1923. It was the first anti-fascist gathering in the UK that carried the word ‘protest’ written in capital letters in the notice that appeared in the Workers’ Dreadnought, the weekly edited by staunch suffrage and political activist Sylvia Pankhurst.

It stated: ‘A PROTEST MEETING AGAINST the Fascist Reaction in Italy and the Camorra de Lospedali in London. Speakers: E. Sylvia Pankhurst, Pietro Gualducci.’

Dondi’s stood at number 24/25A Eyre Street Hill in the heart of Clerkenwell’s Little Italy and was described as a bowling club run by a family of Italians. Most of that part of the district has vanished, but this building remains miraculously intact. Today, it has the name of Gunmakers, a pub that retains a rear section where customers would once play the game of bowls. This must have made the Italian descendants from families who had gravitated to that area since the 1850s feel at home.

Political refugees

What had brought Pankhurst to this meeting with the Italian community of Clerkenwell? The answer is that she had kept track of the development of fascism in Italy from the start and was the first well-known public figure in Britain to denounce Mussolini’s Fascist Party as a criminal organisation.

This had happened through the contacts she had established with a number of Italian political refugees in London – mostly communists and anarchists, whose presence she had probably detected at an early stage as they had been extremely vocal in opposing the First World War.

Pankhurst would have heard of Errico Malatesta, for instance. He was making news to the extent that, when he was arrested and threatened with deportation, the British trade unions arranged for a large demonstration in his support that culminated in Trafalgar Square.

Another political exile, Silvio Corio, was a close friend of his. Corio was a talented typographer and a journalist who gained a lot of attention for his investigative journalism. Pankhurst would certainly have read his articles, which suggested that Fleet Street newspaper proprietors had made fortunes through their support of the slave trade, and denounced atrocities committed by Italian soldiers during the invasion of Libya, which were published in the independent socialist daily the Daily Herald.

It was Corio and his friends who had alerted Pankhurst to the birth of fascism in March 1919. Corio had grown up in Turin, one of Northern Italy’s major industrial towns, where labour unrest had erupted soon after and metal workers, in particular, held protests and set up workers’ councils, in what seemed like the prelude to a revolution. Armed Blackshirts were already at work attacking trade unions and left-wing newspaper offices.

In October, Pankhurst and Corio travelled to the city to take stock of the situation. She met Marxist philosopher and writer Antonio Gramsci and, although they did not see eye to eye on the best way to bring about a revolution, the visit clearly had a strong impact on Sylvia. She then travelled to Bologna, where she attended the congress of the socialist party and witnessed violent clashes involving Mussolini’s supporters. She was quick to detect an indication of worse to come. Leaving Corio behind, who was being pursued by the police and feared being arrested at the border, she left the country, apparently crossing the Alps on foot.

Menace

Corio finally joined her in London and, through the Workers’ Dreadnought, they were the first to ring the warning bell about the fascists, describing them as a bunch of terrorists who presented a menace not only to Italy but to the rest of Europe.

Both Pankhurst and Corio took notice of the creation in London of a branch of the Italian Fascist Party at the end of 1921. It held its first congress on 15 January 1922 at the International Sporting Club at 25 Noel Street in Soho, and they reported on the first march of Italian fascists to Westminster Abbey in the autumn of the same year.

One of the first public meetings attended by Pankhurst in London, organised specifically to denounce ‘the fascisti dictatorship’, took place on 13 January 1923 at the same address where the fascist event had taken place. She spoke alongside political refugees, such as anarchist Vittorio Taborelli, recently arrived from Italy after the fascists had threatened his family, and Pietro Gualducci, an anarcho-syndicalist who had been threatened with deportation and who was the subject of a bulky file held by Scotland Yard.

After this came the ‘protest meeting’ at Dondi’s on 25 March, just one month after the ‘Black Shirt Gala Ball’, a dance event organised by the London Branch of the Italian fascist party held at the Cecil Hotel in the Strand on 25 February 1923 ‘in aid of the fund for the fascista home in London’. The ball was organised ‘under the Patronage of the Italian Ambassador to the Court of St James, Marquis Della Torretta of the Princes of Lampedusa’, with the Italian Military and Naval attachés in attendance. It was probably intended as a celebration of Mussolini’s March on Rome that had taken place five months earlier.

In Italy, opponents of fascism were being attacked, tortured and killed, while in London the fascists were dancing.

Mobilised

There was more than enough to enrage the group of Italian anti-fascists based in Clerkenwell and Soho, which included Corio, Gualducci, Emidio Recchioni, Francesco Galasso, Decio Anzani among others. They had started to mobilise against the fascists in July 1922 with the launch of their own weekly, Il Comento, which branded Mussolini as a bandit and leader of an association of delinquents.

Through her friendship with Corio and Gualducci who were both contributors to Workers’ Dreadnought, Pankhurst was ready to join them publicly to add her revulsion at what was happening not only in Italy but also in London. The fascists were planning to organise the Italian community in the UK, which at the time numbered about 20,000, into what was described as a ‘state in miniature’.

This meant the annexation of all existing Italian organisations in the UK: schools, social and cultural centres and trade unions. Even the Italian hospital (misspelt as ‘Lospedali’ in the notice advertising the meeting) was to be put under the control of the fascist party. In editorials published by L’Eco d’Italia, the Italian fascist weekly in London, the warning to the Italians in the UK was spelt out in capital letters: ‘OBEY.’

It is easy to imagine the sense of urgency behind the decision to hold the protest meeting at Dondi’s to denounce the violent methods that were being used to subjugate the community, drawing comparisons with those used by a Mafia organisation, the ‘camorra’.

At a distance of 100 years the re-enactment of that meeting in the same building, virtually unchanged, was organised by the Pankhurst Memorial Committee, which continues its 25 year-old campaign to have a statue of Sylvia Pankhurst erected in Clerkenwell Green, opposite the Marx Memorial Library and a short distance from the old Little Italy.

This is the perfect choice of place: it illustrates the link between Pankhurst and the Italian community. It also gives due consideration to the tireless efforts of Pankhurst and her friends in the campaign against fascism – from the setting up of the Giacomo Matteotti Committee in memory of the socialist MP assassinated by the fascists to the launch of the weekly New Times and Ethiopia News to condemn the invasion of Ethiopia. Pankhurst’s was a lifelong commitment to anti-fascism that she pursued creatively and with tenacity, never yielding to threats or intimidation.

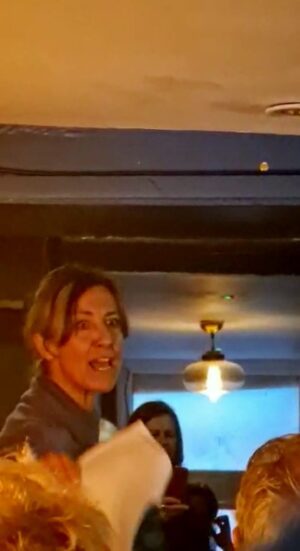

Emma Beattie as Sylvia Pankhurst, 2023

Actor Emma Beattie narrated a speech based on Pankhurst’s articles from the Workers’ Dreadnought, ending with the exhortation to remain vigilant. It was left to the audience’s imagination to navigate the distance between past and present and take stock of the warning bells that had gone unheeded 100 years ago.

‘The deeds of pioneers are calling to us to do something,’ wrote Pankhurst as early as 1919, ‘to do, not waste our lives in dull inaction. How urgent it is, how terribly urgent’.

The maquette for the statue of Sylvia Pankhurst planned to be

installed in Clerkenwell Green

A ‘people’s statue’ for Sylvia

The campaign to erect a statue to commemorate Sylvia Pankhurst began 25 years ago when four women trade unionists – and members of the National Assembly of Women – questioned why there was no statue of this outstanding suffragette to honour her commitment to peace, and her fight against racism, fascism and imperialism.

Thus was born the Sylvia Pankhurst Memorial Committee, bringing trade unions and individual supporters together. College Green outside Parliament was the original site chosen but, although planning permission was granted by Westminster Council, it was rejected by a House of Lords committee.

Now the Committee – Philippa Clark, Mary Davis, Megan Dobney and Barbara Switzer – hopes to see ‘a people’s statue’ unveiled before long in Clerkenwell Green with the support of Islington Council.

As progress is made, the Committee is finalising the funding needed to erect the statue, which has already been cast, and will welcome donations.

To contribute, visit https://sylviapankhurst.gn.apc.org/donate and see @sylviastatue