This article originally appeared here on 14 June. It has been updated to include the far right realignments in the European Parliament following the elections. It also appears in the Summer 2024 issue of Searchlight,

Shock gains for far-right parties right across Europe saw France face a snap election and Belgium’s PM resign. Although the right fell short of its hoped-for majority, the centre is in trouble – and that is bad news for all of us.

By Martin Smith

The evening the European Parliamentary election results for France were announced, Marine Le Pen held a party at a swanky nightclub in the woodlands of the Bois de Vincennes, east of Paris. It was a select gathering of dignitaries from the far-right Rassemblement National (RN). In attendance was the party’s poster boy, Jordan Bardella.

They had cause to celebrate. Le Pen’s RN had won 31 per cent of the vote, gaining 30 European Parliamentary seats (a 12-seat increase on the previous European election), whereas President Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance Party lost more than half its previous seats and votes.

The results were a crushing blow for Macron. A jubilant Le Pen declared at her celebration: “We are ready for power if the French people put their trust in us.” Bardella pushed even harder: “The President of the Republic cannot remain deaf to the message sent this evening by the people of France.” He went on to demand that Macron call an early election.

Macron’s response to the gauntlet thrown down by Bardella was quick, unambivalent and risky. Announcing a snap election, he said: “I’ve heard your message and I will not let it go without a response. France needs a clear majority in serenity and harmony, I cannot resign myself to the far right’s progress in France and everywhere in the continent.”

His statement is revealing, both acknowledging the scale of the vote for the RN and the rise of the far right across Europe. The RN’s results should not be downplayed, they were a huge blow for the centre parties of Europe. It is with some justification that Macron thinks that France is the powerhouse of the European Union (EU) and he is the driving force of the centre parties.

Far-right gains

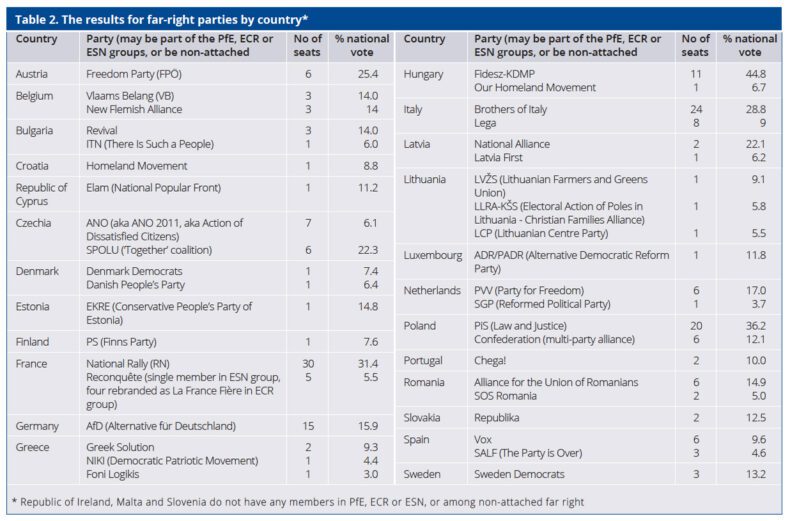

The French results were the high point for the far right in Europe, but there were many other significant results (see tables). Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s fascist Brothers of Italy more than doubled its seats in the EU parliament, coming first with 24 seats, securing 29 per cent of the national vote.

An overjoyed Meloni stated that she was “emboldened by the results” and vowed to play a fundamental role in Europe. Despite a strong challenge, Viktor Orbán’s populist far-right party Fidesz topped the Hungarian polls, winning 11 seats and gaining 45 per cent of the vote. In Austria, the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ) came first, winning six seats and gaining over 25 per cent of the vote. Finally, Belgium’s Vlaams Belang (VB) came joint first with three seats.

In Poland, although Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s centrist Civic Coalition (KO) came first with 37 per cent, the total vote for the far right was significantly larger. The right-wing populist PiS (Law and Justice) ran Tusk close, winning 20 seats (36 per cent), and the fascist far-right multi-party alliance Confederation (Konfederacja) came third, winning six seats and taking 12 per cent of the vote.

Several far-right parties also came second or third. The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) was rocked by scandals involving its candidates’ support for the Nazis in the run-up to the election. Despite this, it still managed to beat German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s centre-left Social Democratic Party to second place.

The AfD won 15 seats, gaining 16 per cent of the vote. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilder’s far-right Party for Freedom (PVV) came second, winning six seats.

Other important votes for the far right included third places for Spain’s Vox and the Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR). In Bulgaria, the ultranationalist Revival Party came fourth in both the EU elections and the parliamentary elections, which were held on the same day.

Shock waves

The levels of support for the far right have sent shock waves throughout Europe. Not only did it force Macron to call a snap election, but Belgium’s Prime Minister Alexander De Croo also resigned after his Flemish Liberals and Democracy Party (Open VLD) suffered a heavy defeat in the European and general elections, both held on the same day. A new government will be formed, and it is unlikely that the far-right populist party VB will be invited to join it, but the new government may coalesce around the separatist right‑wing New Flemish Alliance (N-VA).

Finally, in Austria a general election is set to be held on 29 September, with the far-right FPÖ currently topping the polls. By September the political map of Europe could be redrawn again.

There were some setbacks for the far right, most notably the decline in support for Fidesz, the Czech Civic Democratic Party and Matteo Salvini’s Lega per Salvini Premier (LSP) in Italy. Despite these setbacks across much of Europe, the far right is in the ascendancy.

Media response

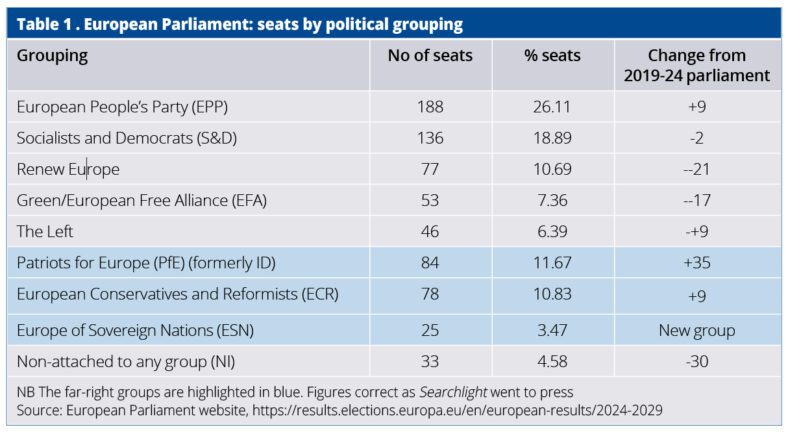

When the results were announced the mainstream media gave a collective sigh of relief focusing on the fact that the centrist parties still hold the majority of seats in the European Parliament (Table 1). This is true: the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) is the biggest bloc, gaining 9 more seats to total 188 compared to the 2019 elections. While the centre-left Socialists and Democrats (S&D) vote remained relatively stable, with only four seats lost, the liberal Renew group was decimated, losing 21 seats, and the Green bloc lost 17 seats.

The idea promoted by the media, that the centre is holding, ignores the far right’s paradigm shift across Europe; its overall vote has increased by 5 per cent. This is part of a long-term trend that has seen the far right making similar size gains in the European elections of 2014 and 2019.

Another area the media has focused on during the 2024 election are the sharp differences between the far-right parties, arguing that it makes it impossible for them to unite. The respected political scientist Cas Mudde reinforced this view, stating in The Guardian: “Although polls predict huge gains for the far right, its deep divisions mean that the victory may prove to be a pyrrhic one.”

Currently, the far right in the European Parliament is found in three formal groupings and among the non-attached odds and sods. The first group is the Le Pen-led Patriots for Europe (PfE), an enlarged rehash of the last parliament’s Identity and Democracy (ID) group; the PfE includes Le Pen’s RN, Vox and PVV plus Fidesz, Chega!, VB and Lega. It has 84 seats.

The second is the Meloni-led European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR); founded by the UK Conservative Party. This is now dominated by the Brothers of Italy, PiS and Sweden Democrats. It holds 78 seats.

The third group is the new Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN), which largely exists to provide a home for Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) members shunned by the ID group over alleged Nazi sympathies (yes, we know, don’t get us started!). With 14 members, AfD is by far the biggest party in this 25-seat group. (A 15th AfD man, the SS apologist and rumoured Chinese intelligence asset Maximilian Krah, has been cold-shouldered and sits among the non-attached radical left and right MEPs).

The three far-right groups might be regarded as the second-biggest bloc in the parliament. Added together, they hold 187 seats, only just short of the European People’s Party’s 188.

There are deep divisions within the ranks of Europe’s far right. Both Orbán and Le Pen have close ties with Vladimir Putin’s Russia and their support for Ukraine and NATO is at best lukewarm. On the other hand, the PiS and Meloni back NATO and are solidly behind Ukraine. It would be in their interests to try to overcome these existing political hurdles and create a powerful far-right bloc in the European Parliament.

These differences should not be downplayed; it is a truism to say that the far right is a band of warring brothers. Yet much unites them: all campaigned on an anti-immigration ticket, in defence of the family and against “gender ideology”.

The growth of the Conservative Political Action Conferences (CPAC) demonstrates the developing links between global extremists and the possibilities of building a right-wing parliamentary block.

Only a decade ago it was widely argued in academic circles that right‑wing electoral parties were strongest in eastern Europe because of the economic and social dislocation produced by the transition from communism to free‑market capitalism. The growth of the far right across western and northern Europe clearly demonstrates that this no longer the case. One of the most worrying developments is the embedding of the far right in the “big three” European powers – France, Italy and Germany.

Wider implications

Far-right parties are shaped by national historical and social issues, but there are also factors that cut across national boundaries. One important factor is the “normalisation” of the far right. The electoral success of all of the far-right groupings has been due to their ability to put forward simple solutions and populist slogans to complex problems.

The key mobilising issue for the far right is its anti-migrant and anti-Islam message. But, instead of challenging the lie that migrants and refugees are responsible for poverty and the decline in services, mainstream parties are copying and introducing their own anti‑migrant/refugee policies.

This is creating a toxic vortex. Thus, we see a legitimisation of the far right, which in turn reinforces the idea that immigration is the problem, which in turn encourages the far right to be even more emboldened in its anti-migrant and racist rhetoric.

During the election, all the main far‑right parties used anti-Semitic tropes (Soros conspiracy theories and talk of global elites) and brazen Islamophobia. They are not, as some claim, diluting their hard-line anti-immigration message, instead they are attempting to popularise it.

Since the end of the Second World War and right up to the late 1990s, mainstream European parties placed a “cordon sanitaire” around the far right. Most politicians refused to debate with their representatives and, with the exception of Italy, parties would not countenance entering into coalition with the far right. This was an important stance; it was a clear demonstration that fascism and right-wing populism were toxic and shared much of the ideological world view of Mussolini and, in some cases, Hitler.

This “cordon sanitaire” is rapidly breaking down. The electoral success of many far-right parties means that many mainstream politicians of the centre right have accepted them into their electoral coalitions.

In the Netherlands, Wilders and the PVV now lead a coalition government, which includes the centre-right People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), the centrist New Social Contract and the Farmer-Citizen Movement (BBB).

In the Swedish Riksdag, the Sweden Democrats have a “confidence and supply” agreement with the centrist government, and in Czechia the right-wing populist Civic Democratic Party (ODS) heads up a coalition with an assortment of Christian Democratic and liberal conservative parties.

With success in the European Parliament elections come massive financial rewards. Every MEP receives a monthly pre-tax salary of €10,075, as well as a general monthly expenditure allowance of €4,950. MEPs also get a monthly budget of €28,696 to cover all costs involved in recruiting personal assistants, and they are reimbursed for their travel and accommodation.

But this is just the tip of the iceberg. Buried in the European Parliament’s website is the annual budget awarded to each European grouping. So, for example, in 2021 the ECR was allocated €4.1 million and the ID €4.6 million. These eye-watering amounts of money will enable the far right to further professionalise their electoral machines, pay full-time organisers, provide access to research and fund their publications.

Traditionally, young people have tended to vote for left-of-centre parties. However, a worrying trend, which was also present in the 2024 European Parliamentary elections, is the growing support among young people for the far right. In France, a poll conducted just before the election revealed that 32 per cent of 18- to 25-year-olds said they would vote for the RN.

Likewise in Poland, exit polls showed the far-right Confederation was the most popular choice with voters aged 18-29 years, polling 31 per cent of the vote. A similar picture can be seen in Belgium where the Flemish far-right VB party is winning support among young men (aged 18-27), nearly 32 per cent of whom said they would vote VB.

Defining the far right

During the election, BBC reporters described far-right parties as either “hard right” or “extreme right”. This does not provide an adequate explanation of their historical roots, ideology or political practice.

We now find ourselves in the bizarre position where the European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen, only labels the ID grouping as far right. In her view, the ECR can be described as a conservative grouping, despite the fact that it is headed by the Brothers of Italy and contains PiS and Vox MEPs.

The danger of von der Leyen ignoring the political make-up of the group is that it downplays the size of the far right in the parliament and also mainstreams them. In this article, we have used the term far right, but if we are going to better understand these parties, we need to be more precise with our terminology.

The first far-right formations in the European Parliament are the right-wing populists, who include Fidesz and the PiS. Outside of the European Parliament you could include Donald Trump and Nigel Farage.

Then there are those that could be described as post-classical fascist parties, such as the Brothers of Italy, RN and the SD. These formations have similar political features to the populist parties: both campaign against migrants, Muslims and elites, and both formations are ultra-nationalistic to their core. Also, when in power they are authoritarian and promote the idea of the strong leader.

However, there are important differences. Mudde has played a key role in developing a conceptual framework to define right-wing populism. He argues that it combines nativism, authoritarianism and populism.

Academics Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin focus primarily on a demand-side explanation to define right-wing populism, which they call the “Four Ds”. These are: (1) “Distrust” of liberal democracy and elites; (2) “Destruction”, the loss of national identity; (3) “Deprivation”, the belief that inequality is growing, and the indigenous population is being left behind; and (4) “De-alignment”, the weakening of the bonds between people and the traditional parties.

Post-classical fascist parties differ from their populist friends in several ways. They have ideological/historical links with previous fascist parties.

Second, in a search for electoral success, they have undergone a process of “modernisation”. Le Pen and her father were the architects of this strategy. It involved cleaning up the party’s public image, dropping aggressive anti-capitalist rhetoric, and toning down its racism and anti-Semitism and instead promoting the ideas of nation rather than race.

Finally, powerful electoral machines have replaced the street thugs. Two things are worth noting: the modernisation strategy undertaken by all post-classical fascist parties has both created internal tensions and splits, and their past adherence to fascism haunts their electoral campaigns.

It is important not to treat these formations as static entities. They are in a constant state of flux and there is a growing cross-fertilisation of ideas between the two traditions. Increasingly, they are prepared to adopt one another’s strategies and policies. Understanding the nature of these parties and the political strategies they develop is not solely an academic exercise, it enables anti-fascists to recalibrate their campaigns and better understand how to undermine them.

For instance, in Britain, when the British National Party (BNP) shifted away from street fighting in the early 1990s and instead made a turn towards winning elections, anti-fascist groups had to change their approach and focus on local issue-based campaigns against the BNP.

Conclusion

The campaign against the far right in Europe has reached a critical phase. Macron’s gamble of calling an early election was relatively successful in the short term. Le Pen’s project was set back, coming third, yet it has 142 seats – something unimaginable a decade ago. The tin can has just been kicked down the road – Le Pen’s sights are clearly set on the French Presidential elections in 2027.

In the UK, the Conservative Party was decimated in the general election; it now has just 121 seats (losing 252 MPs). But it is deeply divided between its traditional “one-nation conservative” grouping and those that include Suella Braverman who want to take the party in a more right-wing populist direction.

These tensions inside the Conservative Party are exacerbated by the rise of Farage and his Reform UK. It won five seats in the July general elections, with 14% of the vote; nationally 4 million people voted for this right-wing populist party.

Since the 1960s, Britain’s far right has made its most significant electoral gains when Labour was in office. That was true in the 1970s when the fascist National Front began to grow and in the first decade of this century when the BNP reached its electoral zenith.

As far as any revival of the far right goes, Britain may only be a few years behind Europe. The emergence of Reform UK and the revival of Tommy Robinson and his street thugs could be a pivot point for the far right in Britain.

Photos from left: Marine Le Pen and Giorgia Meloni who were jubilant when the polls results came in; Viktor Orbán whose Fidezs topped the polls in Hungary; Geert Wilders whose far-right PVV secured the second highest number of votes in the Netherlands.

Credit: Wilders photo, Prachatai