The red triangle was in the news recently when the city of Berlin senate banned its use on activities related to the Middle East after the image was appropriated by Hamas supporters.

There is some confusion as to the origins of the use of the red triangle in this context with some saying it represents the red triangle of the Palestinian flag and others that it comes from the videos produced by Hamas’s Al-Qassam Brigade where it is often used to identify the enemy.

In addition to being used on social media and demonstrations it has been used as graffiti, including on Jewish people’s homes, as an act of intimidation.

The anti-fascist red triangle

It’s frustrating seeing the red triangle being used in this way because since the end of the Second World it has been an anti-fascist symbol. This is the case most notably in Germany, where former political prisoners in Nazi Germany who were forced to wear it on their concentration camp uniforms, turned it into a badge of anti-fascist pride.

The triangle is part of the logo of the Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes – Bund der Antifaschistinnen und Antifaschisten (VVN-BdA) – the Association of Persecutees of the Nazi Regime – Federation of Antifascists – (centre) which was formed in 1947.

Originally dominated by communists – for it was they who had been incarcerated – it is the largest and oldest anti-fascist organisation in Germany.

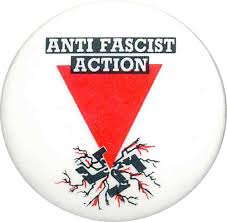

It wasn’t only in Germany that the red triangle was an anti-fascist symbol. It was also an anti-fascist symbol in Britain. Anti-Fascist Action used the symbol in the 1980s with the red triangle piercing a swastika (right).

That particular image harked back to early Soviet propaganda. In 1918 Nikolai Kolli produced a sculpture of a red wedge (left) piercing and cracking a white block, the block representing the “Whites”, supporters of the Tsar and other reactionaries who opposed the Bolshevik Revolution.

The avant-garde Russian Jewish artist El Lissitsky echoed that sculpture in his famous “Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge” poster, some arguing that the slogan was chosen to counter the Russian pogromist slogan “Bej zhidov!” (“Beat the Jews”).

Berlin 1988: the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht

It was in West Berlin in 1988 that I met members of the VVN – as it was then – at an international anti-fascist conference which coincided with the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht, the mass pogrom initiated by the Nazis.

In those days, long before Holocaust Memorial Day was established on January 27th, it was commonplace to mark November 9th to remember the victims of Nazism.

Concentration camps

In fact, the German anti-fascists preferred to call it “Pogromnacht” as Kristallnacht was the Nazis own term for the atrocity and downplays what happened as being a “night of broken glass”.

In fact, on November 9 and 10, 1938, Jewish homes and shops were ransacked, and synagogues destroyed. Jews were forced to pay for the damages inflicted upon them. People were tortured in the streets and as many as 30,000 sent to concentration camps.

They often called themselves Antifa and were certainly the forerunners of what is known as Antifa today using the same imagery of black and red flags in the 1980s that Antifa use today

Graeme Atkinson, who was the European Editor of Searchlight at the time and busy building what was to become an important international anti-fascist network, was involved with organising the conference and somehow managed to convince the Union of Jewish Students (UJS) to send me as a delegate.

I was still a teenager – nineteen years old – and at the end of a term of serving as their national anti-racism officer. As well as the conference there was a demonstration, and I addressed the rally, giving greetings from the UJS.

It’s kind of hard to get your head round this but West Berlin was a capitalist island in the DDR, East Germany. West Berlin was formally controlled by the Western Allies and surrounded by the Berlin Wall. The unusual status of the city meant that West Germans could avoid being drafted for compulsory national service by going to live there.

Antifa imagery

As a result there was many young left wingers living in squats in Kreuzberg and elsewhere that comprised what was known as the Autonoms – independent anti-capitalist leftists who also had little time for what they saw as the repressive East German regime.

To us Brits they resembled anarchists, although they weren’t anarchists in spite of their direct action approach to politics.

They often called themselves Antifa and were certainly the forerunners of what is known as Antifa today using the same imagery of black and red flags in the 1980s that Antifa use today.

East Germany

The DDR Conference delegates were welcomed into the DDR for a tour of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. We were taken in by coach and as official guests of the government all the usual visa requirements were wavered.

We had a meeting with officials and were then given a tour of the camp. The handful of English language speakers were given our tour by an English-speaking former inmate, Werner Händler.

He explained the central role the camp played in the entire camp system. It was the first time I had visited a concentration camp and was a deeply moving experience.

Path to reunification

That was November 9 1988, 50 years after one of the most significant events on the path to the Holocaust. There was no indication that exactly one year later, November 9 1989, the Berlin Wall would be torn down with Germans celebrating in the streets as the path to reunification began.

Amid the celebrations many forgot why Germany was divided in the first place, but not those who had worn the red triangle.