In a lifetime of political thuggery, fraud and nepotism, Jean-Marie Le Pen (who has died aged 96) typified fascist politics. We shouldn’t be surprised that he became a hero for his far less successful British imitators.

Le Pen acquired his first criminal record as a teenager beating up opponents on the streets of Paris, where he sold papers for Action Française, whose antisemitic leader Charles Maurras was in prison for wartime nazi collaboration.

Happy to inflict or incite violence

For the rest of his life Le Pen was happy to inflict or incite violence as part of his stock in trade, whether against the left, or Algerians (whom he tortured as a French colonial intelligence officer in the mid-1950s), or Jews (whom he persistently baited with Holocaust denying rhetoric), or other French citizens descended from immigrants.

Last year Le Pen was able to use his age and apparent declining faculties to dodge a last set of criminal charges for misappropriation of public funds, part of a wider case against his daughter Marine Le Pen and her party National Rally (Rassemblement National) which she developed out of her father’s National Front.

But this final attempt to rip off European taxpayers was characteristic of Le Pen’s entire career. He succeeded in building a party that was entirely under his personal control and which supported a lavish lifestyle for the Le Pen family.

Those who built the FN after 1972 with Le Pen included terrorists who had tried to assassinate President Charles de Gaulle in the early 1960s, as well as veterans of Vichy and fanatical antisemites from the schismatic Catholic sect Society of St Pius X.

This history of nepotism contributed to numerous splits that weakened the National Front but never quite killed it. Le Pen inherited and built on a certain tradition of xenophobia (including antisemitism) in French politics, which can be seen from the infamous Dreyfus case of the 1890s, through the fascist movements of the 1930s and the eager collaboration of many French conservatives with the nazis and their Vichy allies.

Those who built the FN after 1972 with Le Pen included terrorists who had tried to assassinate President Charles de Gaulle in the early 1960s, as well as veterans of Vichy and fanatical antisemites from the schismatic Catholic sect Society of St Pius X.

Admirer of Holocaust deniers

Le Pen was known to be an admirer of Holocaust deniers including his fellow Frenchman Robert Faurisson. Beginning in 1987, he made a series of remarks belittling Holocaust history that led to several criminal convictions. In 2015 he defended Pétain’s Vichy regime in an interview with the leading far right publication Rivarol which has close ties to Faurisson and other Holocaust deniers as well as to the broader European fascist scene.

That interview provoked his own daughter Marine to expel Le Pen from the National Rally party. She had taken over the National Front from her father and renamed it, but has herself continued a pattern of associations with extremists. Anti-fascists have observed that Marine Le Pen seems engaged in a constant balancing act, one minute appearing “moderate”, the next sending signals to her party’s fanatical base.

Her own attempts to build connections with mainstream conservatives in the UK follow her father’s footsteps. In 1987 Jean-Marie Le Pen was invited to a fringe meeting at the Conservative Party conference, only to be disinvited after strong anti-fascist protests.

Welcomed to the UK

In the late 1990s members of several factions on the British and American far right attended Le Pen’s “Bleu, Blanc, Rouge” carnivals in a Paris suburb. Jared Taylor from the US racist magazine American Renaissance joined the publishers of Right Now magazine, British barrister Adrian Davies and fascist turned country gent Derek Turner. Also quaffing champagne was a rival delegation from what was then John Tyndall’s BNP, including Richard Edmonds and (on a later trip) Nick Griffin.

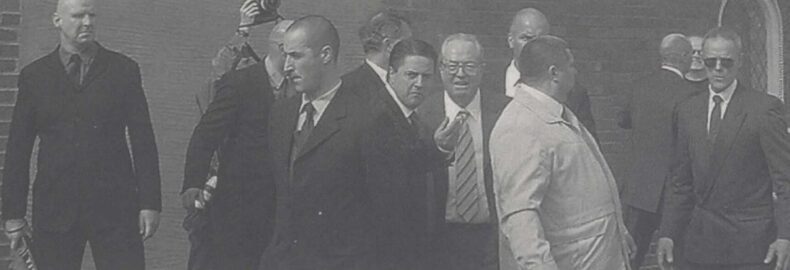

It was Griffin who was the first British political leader to welcome Le Pen to the UK in April 2004 (below). His security team included Merseyside gangster Joe Owens and Glaswegian Combat 18 thug Steve Cartwright.

Griffin tried to emulate Le Pen by centralising power in his own hands and giving jobs on the party payroll to members of his own family. But while Griffin ended up bankrupt, Le Pen built up the strongest political family business in Europe.

In 2002 the fragmentation of French mainstream politics allowed Le Pen to get into the second round of the French presidential election after taking 4.8 million votes (16.9%) in the first round, but he was barely able to increase that total in the second round and lost by an 82-18 margin to the conservative incumbent Jacques Chirac. In his final presidential contest five years later, Le Pen’s first round vote slipped to 10.4%.

Jean-Marie Le Pen stood with one foot in 20th century fascism – the barely disguised, ranting, antisemitic thug – and one foot in its 21st successor

Those results epitomised the extent to which Jean-Marie Le Pen stood with one foot in 20th century fascism – the barely disguised, ranting, antisemitic thug – and one foot in its 21st successor – the besuited ‘dissident right’ exploiting populist discontent.

He probably knew that he would never escape his past or shed his street-fighting image. It remains to be seen whether anti-fascists can mobilise opposition to his subtler successors, including his own daughter.