As Reform UK rides a surprising wave of electoral support across parts of England, the party’s populist rhetoric and its leader’s controversial foreign policy stances deserve renewed scrutiny.

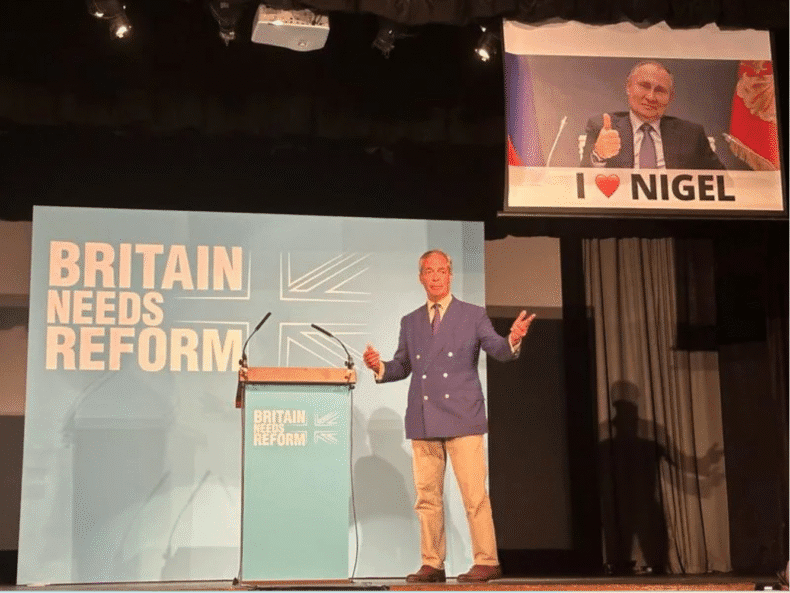

Nigel Farage, the face of Reform and the prime political figure synonymous with Brexit, has long portrayed himself as a crusader against establishment politics. But his pronouncements on Vladimir Putin and Russia suggest an affinity that goes beyond mere contrarianism.

Now, with Reform UK gaining ground, the implications are more serious than ever.

Kremlin talking points

Farage’s ambiguous stance on Russia is not new. In 2014, during a period of heightened tensions over Crimea, Farage stunned many by naming Putin as the world leader he most admired—not for his ethics or democracy, but as a political “operator” who, in Farage’s view, outplayed Western powers over Syria.

Though Farage qualified his remarks by condemning Putin’s record on press freedom and human rights, the comment signalled a preference for strongman tactics over liberal diplomacy.

Since then, Farage has repeatedly echoed Kremlin talking points. Most notably, he argued that NATO and EU expansion “provoked” Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a claim strongly condemned across the political spectrum.

Keir Starmer went as far as accusing Reform UK of “fawning over Putin,” a damning charge in a geopolitical climate where solidarity with Ukraine remains a moral litmus test.

Parroting the Kremlin worldview

Farage’s critics also point to his appearances on RT (formerly Russia Today), a state-controlled network known for disinformation campaigns. Farage has dismissed such concerns as smears, insisting his views are grounded in realism.

Yet, as he courts disaffected voters with promises of national renewal, questions persist: why does he so often seem to parrot the Kremlin’s worldview.

Further complicating the picture are Farage’s connections during the Trump era. In 2017, The Guardian revealed that Farage had been named a “person of interest” in the FBI’s Russia investigation—someone who was not suspected of criminal activity, but who might have had knowledge useful to the probe.

His public associations with figures like Trump ally Roger Stone and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange have drawn media attention and speculation that Farage was closer to the transatlantic populist–authoritarian nexus than previously acknowledged.

Casting a long shadow

Although no hard evidence of wrongdoing has emerged, the pattern of associations, statements, and media appearances casts a long shadow. Reform UK may be the beneficiary of legitimate voter anger, but the geopolitical leanings of its leader merit concern.

Electoral success should not immunize Farage from scrutiny, especially when his positions appear to align more with Moscow than with Westminster.

As Reform UK aims for a breakthrough in the next general election, the British public must consider not just what the party stands against – but what, and who, it stands beside.