The Labin Uprising of 1921, often heralded as the first anti-fascist revolt and workers’ republic in Europe, is a landmark in miners’ history.

Taking place in the Istrian town of Labin, now Croatia, then under Italian rule, this often-overlooked miners’ uprising showcased the power of workers’ solidarity and foreshadowed the anti-fascist struggles that would engulf Europe in the decades to follow.

Early stirrings of fascist ideology

After World War I, Istria was handed to Italy under the 1920 Treaty of Rapallo. This changing of the map marked the beginning of Italian rule, under which the Croatian and Slovenian populations of Istria faced cultural suppression, economic exploitation, and the early stirrings of fascist ideology.

Italianisation policies targeted local languages and identities, while economic conditions declined for workers and peasants alike.

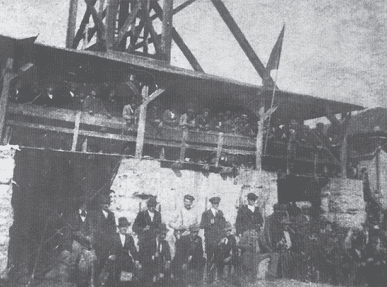

The coal mines in the Labin part of the Istrian coalfield – three underground collieries employing 2,000 men – reflected these tensions, the miners enduring perilous working conditions, meagre wages, and exploitative practices.

The situation at the collieries worsened with the appointment of Italian managers, who introduced discriminatory policies favouring Italian workers over the local labour force.

Shaping the intellectual environment

This marginalisation and economic hardship fuelled growing dissatisfaction among the miners and set the stage for the uprising.

Giuseppina Martinuzzi was a kind of Mother Jones playing a key role in shaping the intellectual environment that underpinned the miners’ resistance.

A socialist and writer from Labin, Martinuzzi was a fierce advocate of workers’ rights and equality. Her writings and activism inspired the labour movement with her vision of a more just society.

Italian rule in Istria coincided with period of heightened class struggle. Across Europe, workers organised strikes and revolts in response to post-WW1 economic instability, rising inequality, and oppressive regimes.

The Labin miners were not alone in their fight but part of a broader tapestry of resistance, including movements in Germany, Britain, and Russia.

The spark

The immediate trigger for the uprising in Labin was the miners’ opposition to wage cuts and the spread of fascist ideology imported from Italy.

On 2 March 1921, tensions reached a breaking point when miners seized control of the coal mines, expelled the Italian management, and declared the establishment of the Labin Republic.

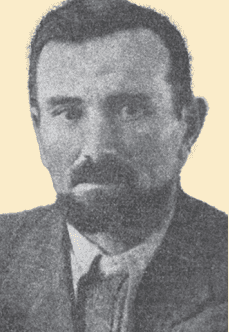

The uprising was a combination of individual and collective efforts. Among the leaders was Ivan Pipan (Giovanni Pippan), a militant trade union organiser who rallied the 2,000 miners around the idea of self-management of the pits.

Tensions reached a breaking point when miners seized control of the coal mines, expelled the Italian management, and declared the establishment of the Labin Republic

The uprising originated in immediate grievances and a deep sense of injustice tied to the miners’ cultural identity.

An important day

One cause of the strike was by the mine owner’s refusal to pay a bonus for February 1921 because the miners had taken a day off to observe the occasion.

For the miners – Croats, Slovenes, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Germans and Hungarians – Candlemas was next to the feast of Santa Barbara as a most important religious day.

The imposition of Italian rule was relentless. Fascists invaded the headquarters of the Workers’ Committee in Trieste early in 1921, set it on fire and attacked representatives of the Raša (Arsa) Mining Trade Union.

The Italian take-over brought with it economic exploitation and cultural erasure. Many miners saw their resistance as a fight for dignity, identity, and autonomy, transcending mere economic demands.

Brutally beaten by fascists

In these circumstances, Pipan was sent by the Italian Socialist Party in Trieste – in the Friuli-Venezia–Giulia region in Italy – to support the Labin miners.

As he made his way, Pipan was brutally beaten by fascists on 1 March 1921 at the Pazin train station.

This was the spark that set the situation alight. Word of the attack on Pipan spread quickly and the miners decided to occupy the mines in protest. Pipan’s ability to articulate and unite the miners’ demands against the Italian authorities was crucial to the uprising’s success.

The miners were determined to protect their collieries and Francesco Da Gioz, emerged to organise and command the Red Guards, the armed defence units formed to protect the miners’ self-governed republic. Originally from Roe Alte in the Veneto region of Italy, Da Gioz had moved to Labin to work as a miner before the uprising.

Apart from reacting to fascist violence, the uprising originated in immediate grievances and a deep sense of injustice tied to the miners’ cultural identity.

The declaration of the Labin Republic on 7 March represented not only an open rejection of Italian authority but also a bold vision for a new society based on workers’ control, equality and collective rule.

For more than a month, the miners ran their mines collectively, organising a system of workers’ self-management.

The slogan Kova je naša! (The mine is ours!) became the movement’s rallying cry, encapsulating their demand for ownership and control over their labour.

This act of defiance was radical in the context of the early 1920s and resonated with broader socialist and labour movements across Europe.

A workers’ experiment

The Labin Republic was a remarkable experiment in self-management. During its brief existence, the miners established a democratic structure to manage the mines, with elected representatives overseeing operations and was a practical demonstration of the miners’ belief that they could manage their own affairs without the interference of exploitative authorities.

The miners also worked to address immediate concerns within their community, ensuring fair working conditions and organising food supplies for workers and their families. In this, they were supported by local peasants.

Women in the mining communities played crucial support roles during the uprising, such as organising food supplies, maintaining morale, and participating in demonstrations.

Community-wide movement

Their contributions highlight the communal nature of the resistance, often overlooked in historical accounts. The Labin Republic was a miners’ revolt but also a community-wide movement that drew strength from collective solidarity.

In addition to ensuring operational efficiency, the Labin Republic became a symbol for envisioning a better world. Workers held assemblies where they debated not just logistical matters but broader questions about governance, justice, and the role of labour in society.

These discussions reflected a growing awareness of global labour struggles and a belief in the transformative power of collective action.

Suppression and aftermath

Despite the miners’ resilience, the Labin Republic was short-lived. By early April 1921, Italian military forces were ordered in to put down the uprising. The miners faced violent reprisals, with over a thousand Italian troops making mass arrests and subjecting the movement’s leaders to harsh punishments in the prisons.

Figures, such as miners Maksimilijan Ortar and Adalbert Sykora, are still remembered due to their tragic deaths on 8 April 1921 during the suppression by Italian army.

Another casualty was Jakov Šumberac Lukić, a member of the Red Guards, who succumbed to pneumonia while guarding the power plant under harsh conditions, making him one of the first known casualties of the uprising.

Today, a monument in his honour stands in the cemetery of Nedešćina, commemorating his contribution to the fight for workers’ rights.

These sacrifices underscore the immense challenges and personal risks faced by those involved in the uprising.

The brutal suppression and resulting fascist terror marked the end of the Labin Republic as a political entity but its significance endured far beyond its brief existence.

The suppression of the Labin Uprising ended the miners’ self-management experiment but not their legacy. The events of 1921 became a symbol of resistance against fascism and exploitation.

The suppression of the Labin Uprising ended the miners’ self-management experiment but not their legacy. The events of 1921 became a symbol of resistance against fascism and exploitation.

In the following years, the uprising’s memory inspired anti-fascist movements, particularly during World War II, when Istria became a site of intense anti-Nazi partisan activity.

The Labin pitmen’s example showed that even under the most oppressive conditions, workers could battle fascism challenge their “masters” and envision an alternative future.

Legacy of an uprising

The Labin Uprising stands as an important moment in the history of resistance. It represents the intersection of labour rights, anti-fascist resistance, and cultural identity.

The pitmen’s demands for self-management were not merely about wages or conditions but about asserting dignity and gaining control over their own destinies.

The Labin Uprising’s centenary in 2021 reignited interest in its legacy. Commemorations, exhibitions, and cultural events brought the miners’ story to a new audience, emphasising its relevance in today’s workers’ rights and justice struggles.

Figures like Martinuzzi and Pipan illustrate how intellectual leadership and grassroots mobilisation can create profound social change.

In his speech to a gathering of thousands, the President of the Republic of Croatia, Zoran Milanović, caught the spirit of the uprising and the mood of his audience:

“Here, in 1921, men — young men—Italians, Croats, Czechs… Citizens… People of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire came together, above all, in a class struggle.

A struggle against injustice, exploitation, and oppression—a fight for fundamental human dignity. It lasted for a month before they were defeated by military force, by sheer power.

Remained autonomous

Their organization was not a strictly hierarchical one, unlike other revolutionary movements that were shaking Europe at the time, and they were certainly aware of this.

They carried a red flag, the hammer and sickle. They had ideals. But above all, in their efforts, in their struggle, they remained autonomous.

This was, quite simply, a fight of ordinary people for a better today and an even better tomorrow.”

As the international working class movement grapples with issues of exploitation and inequality, the Labin Republic remains a powerful example of what collective action can achieve.

The story of the uprising also serves as a testament to the enduring importance of solidarity and resistance in the face of systemic oppression.

The Labin Republic was an historical milestone and a call to action for future generations to stand up against exploitation and inequality.

Through their heroic defiance, the miners of Labin proved that even in the most challenging circumstances, ordinary people can rise to shape the course of history.

The author is the son of a Durham miner and is indebted to his friends and comrades in Zagreb – Cvijeta Senta and Nenad Pavik – for their research, solidarity and kindness. This article first appeared in the brochure of the 2025 Durham Miners’ Gala and we are grateful to the Durham Miners’ Association, the Friends of Durham Miners’ Gala and DMG brochure editor Dave Temple.