Christian nationalism is not just a theological position. It is a political weapon – a reactionary ideology that fuses religious fundamentalism with racial exclusion, patriarchal control, and authoritarian ambition.

Born in the United States and steeped in white supremacist theology, it has begun to seep into British political discourse, often under the guise of “defending Christian values.”

American origins

Christian nationalism in the U.S. emerged from a toxic blend of settler colonialism, racial capitalism, and religious exceptionalism. It asserts that America was founded as a Christian nation, chosen by God to uphold biblical law.

This myth has long been used to justify violence – from the genocide of Indigenous peoples to the defence of slavery and segregation.

During the Cold War, Christian nationalism gained institutional traction. “In God We Trust” was adopted as the national motto in 1956, and religious rhetoric was weaponised against civil rights, feminism, and secularism.

The early Religious Right, led by figures like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, built a political machine that merged evangelical Christianity with Republican conservatism.

Their targets were clear: abortion rights, LGBTQ+ equality, racial justice, and any challenge to white patriarchal authority.

Last weekend, in Kansas, people gathered to remember Leonard Zeskind, who died in April and was for many years Searchlight’s US correspondent. He was also a dear friend and collaborator.

His seminal book, Blood and Politics, remains one of the most important investigations into the white nationalist movement in the U.S, exposing how Christian nationalism is not merely cultural nostalgia, but a theological justification for racial hierarchy and fascist organising.

Strategic camps

Lenny, a MacArthur Fellow and long-time researcher of extremist groups, investigated the period from the mid-1970s onwards, when white supremacist organisations fractured between two strategic camps: “mainstreamers”, who softened rhetoric to gain broader political legitimacy, and “vanguardists”, who pursued militant separatism and insurrectionary goals.

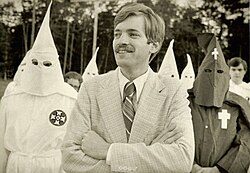

The book profiles key figures such as KKK leader David Duke, Liberty Lobby’s Willis Carto, and William Pierce, who set up the National Alliance and wrote the Turner Diaries which inspired the Oklahoma bombing of 1995.

Lenny highlights how strands of Christian Identity theology – rooted in claims that white Europeans are God’s chosen people and Jews are satanic impostors – provides a religious justification for white nationalist movements.

This fusion of racial and religious identity allows extremist leaders to frame their cause not just as political, but as divinely ordained.

Reimagining white Europeans

Virulently racist and antisemitic, this theology reimagines white Europeans as the “true Israelites” and non-white people as subhuman.

It has inspired paramilitary groups and domestic terrorists as well as more orthodox far-right movements and activists. It is not fringe, but a foundation stone of American white nationalism.

While the UK lacks the constitutional religiosity of the U.S., it is becoming increasingly vulnerable to Christian nationalist influence.

Far-right groups like Britain First and UKIP have adopted Christian symbolism to frame their anti-Muslim campaigns. Their use of crosses, crusader imagery, and “Christian heritage” is not theological, it is cultural warfare.

US backers

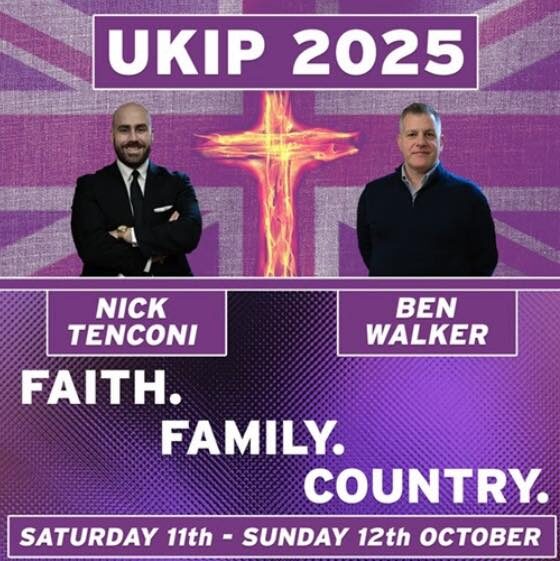

One of the main vehicles importing U.S style-Christian nationalism to the UK has been Turning Point, still run in this country by UKIP leader Nick Tenconi, and with some membership overlap between the two organisations.

When Turning Point USA launched its British offshoot in 2019, it hoped to bring the firebrand energy of America’s campus culture wars to UK universities.

Backed by US donors and fronted by slick social media campaigns, Turning Point UK (TPUK) set out to challenge what it called “left-wing indoctrination” in schools and lecture halls.

Initial support from Conservative figures such as Jacob Rees-Mogg and Priti Patel gave the project a veneer of legitimacy. But the group quickly became a subject of ridicule and and its student agitation sank pretty much without trace.

High profile

By 2021, under Nick Tenconi’s leadership, TPUK shifted away from campus activism towards street demonstrations, working more closely with other far-right organisations.

Its most high profile initiative has been the demonstrations it organised at the Honor Oak pub in south London in 2023, against Drag Queen Story Hour, where it linked up with extremists from Combat 18 and British Movement.

Religion is a central part of Turning Point’s ideological DNA. In the US, its late founder Charlie Kirk frequently invoked “Judeo-Christian values” as the bedrock of Western civilisation, while the organisation has partnered with evangelical networks and aligned itself with campaigns against abortion and LGBT+ rights.

This religious framing has been echoed in Britain, where TPUK demonstrations often feature Christian imagery and rhetoric about defending “Christian civilisation” against secularism and immigration – and particularly against Islam.

Limited impact

Ultimately, TPUK’s limited impact underscores the cultural gap between US-style activism and UK political realities. But its presence on the UK far-right scene highlights the porousness of political culture across the Atlantic, where ideas and tactics migrate even if they struggle to take root.

This, however, has not discouraged Tenconi from transforming UKIP into a similar vehicle for Christian nationalism, now positioning itself as the voice of the new Christian right.

But there are also signs that Tommy Robinson’s Islamophobic ‘cultural movement’ is on the verge of a developing into a far-right Christian crusade.

Holy encounter

In Israel last month, Robinson announced that he had an encounter with the Holy Spirit. His close ally Liam Tufts was actually baptised in the River Jordan during the visit, and Robinson later lamented that he had not take the plunge as well.

Richard Inman, one of his veteran organisers, has been playing the God card for some time and Rikki Doolan, who regularly appears on Robinson’s platforms, runs his own church in north London which Robinson announced a few weeks ago he would be attending (he didn’t).

Possibly the most ridiculous conversion has been that of Robinson’s close mate, Danny Tommo, convicted drug dealer and kidnapper (at knife point) and the man who urged online that “every city must go up” after the Southport murders last year. He now describes himself as born again and “Trusting in Jesus Christ, Our Saviour”.

He has been at the forefront of a number of incidents at Speakers Corner, in London, where gangs waving crosses and chanting “Christ is King” have aggressively confronted Muslim speakers.

This is Christian nationalism stripped of doctrine and repurposed as a racialised marker of Britishness, used to exclude migrants, Muslims, and anyone deemed “un-British.”

Parliamentary inroads

Elements within the Conservative Party have also now begun echoing Christian nationalist talking points. MPs speak of “reclaiming British values,” resisting “woke ideology,” and defending “traditional families.” These are not neutral statements but ideological signals aligned with a global far-right agenda.

Think tanks and pressure groups with links to U.S. Christian conservatives are increasingly active in Westminster. Their influence is subtle but growing, shaping debates on education, gender, and civil liberties.

Confront this

Anti-fascists must confront this Christian nationalism head on. That means exposing its theological roots, challenging its cultural symbols, and exposing how far from genuine Christianity it actually is. It means refusing to let “Christian values” be weaponised against marginalised communities.

It means being alive to how, if it is not opposed, it can drift from the fringes to the mainstream – a process which has already begun.