This week, the German courts were again having to confront the case of the terrorist National Socialist Underground, which went on a rampage of racist murders a quarter of a century ago.

At a hearing to consider the process of releasing Beate Zschäpe, a founder of the group, the daughter of one of its murdered victims confronted her in the courtroom.

Legal wrangling

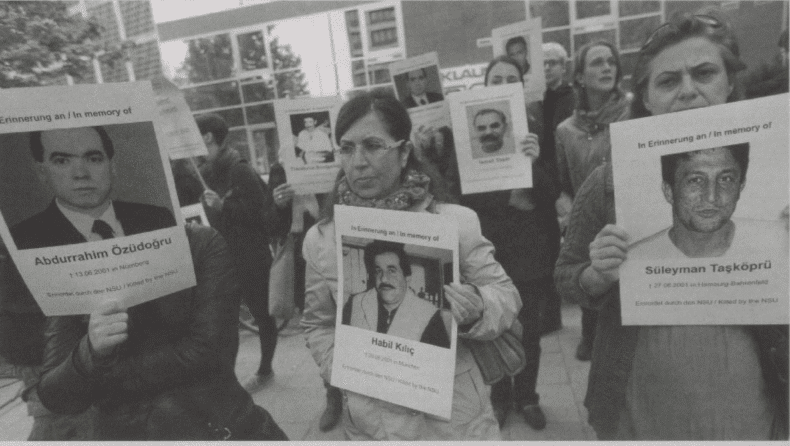

Semiya Şimşek’s words cut through years of legal wrangling: “This makes us feel worthless once again in Germany. Beate Zschäpe, a criminal, is given more value than the victims.”

Her intervention came as outrage mounted over Zschäpe’s admission into a deradicalisation programme that could pave the way for early release.

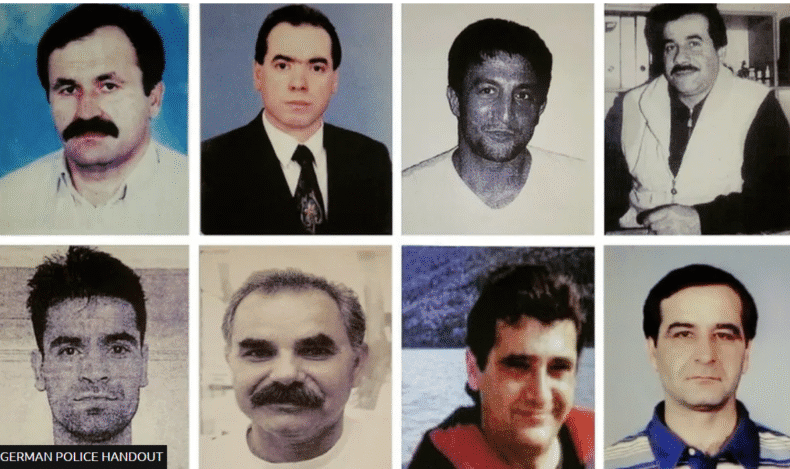

The shadow of the NSU stretches back to the early 2000s. Between 2000 and 2007, ten people were murdered, nine of them men of immigrant background, killed in cold blood, the other a police woman.

In 2004, a nail bomb exploded in Cologne, injuring twenty-two, yet police dismissed racism as a motive.

Failed bank robbery

The group’s existence was only revealed in 2011 after two of its founders, Uwe Mundlos and Uwe Böhnhardt, killed themselves following a failed bank robbery, and Zschäpe set fire to their flat in Zwickau.

Zschäpe surrendered days later, having mailed a grotesque DVD to newspapers and Muslim organisations in which the NSU claimed responsibility for the killings and the Cologne nail bomb attack.

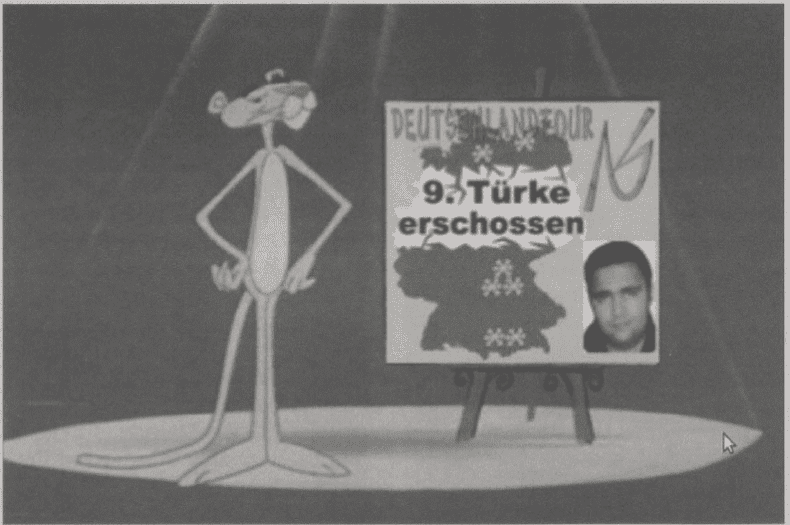

Pink Panther

The video, set to the Pink Panther theme, interspersed cartoon clips with images of victims lying in pools of blood. After her arrest, Zschäpe remained silent, leaving her role and motives shrouded in mystery.

Zschäpe’s path into extremism began in Jena, where she grew up in a fractured family and gravitated towards the militant Kameradschaft Jena.

Alongside Mundlos, Böhnhardt and Ralf Wohlleben, she immersed herself in Thüringer Heimatschutz, which by the late 1990s had become Thuringia’s most militant neo-nazi organisation.

This network became her surrogate family and the foundation for a campaign of racially motivated murders, bombings, robberies and arson.

Life imprisonment

The Munich trial that followed, lasting from 2013 to 2018, eventually sentenced Zschäpe to life imprisonment, but survivors and bereaved families were left with many unanswered questions and little sense of closure.

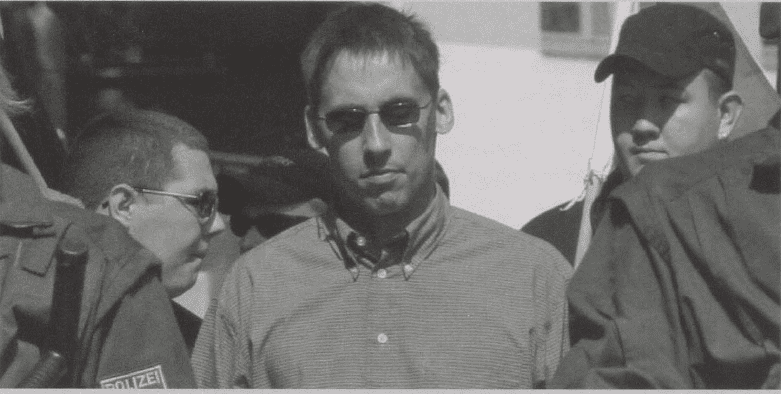

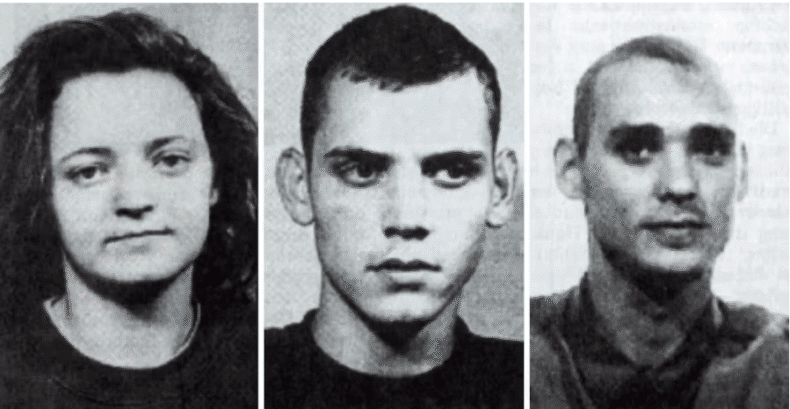

Five defendants stood accused of founding or supporting the NSU. At the centre was Zschäpe, 38, the only surviving member of the founding trio.

The others who stood in the dock with her were:

- Ralf Wohlleben, deputy chairman of the NPD in Thuringia, accused of supplying the murder weapon.

- Holger Gerlach, who provided false documents and rented vehicles used in attacks.

- Carsten Schultze, who delivered the Česká pistol via Wohlleben.

- André Eminger, who arranged safe houses, assisted robberies and produced the Pink Panther video.

The NSU cell went undetected for more than a decade, leading to accusations that the police and security services had made serious mistakes in their investigations.

Police later admitted that they had failed to consider the possibility that the killings were racially motivated.

For a long time, the crimes were treated as isolated incidents, assumed to be the result of feuds within Germany’s Turkish community.

Documents shredded

The trial caused considerable embarrassment for Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, the Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV), after it emerged that the agency had shredded documents following the NSU’s exposure, possibly in an attempt to cover up aspects of its investigative role.

The revelations forced the resignation of the BfV’s head, Heinz Fromm.

Some reports suggested that the shredded files concerned undercover agents linked to the organisation from which the NSU had emerged in the German state of Thuringia.

Undercover agents

According to estimates by a lawyer representing one of the victims’ families, around 30 undercover agents were active in the NSU’s environment.

Evidence indicated that at least two undercover agents had suggested to the BfV how the trio could be captured, but no action was taken.

Zschäpe remained silent until two and a half years into the trial.

Then she denied having been involved in any of the killings, blamed them all on her two accomplices and described herself as their “11th victim”.

She remained stony-faced and impassive when the court heard heartbreaking testimony from the victims’ families.

No remorse

Unsurprisingly, there is now anger at her possible release.

Families argue she has shown no remorse, offered no answers about accomplices, and continues to manipulate the system.

A petition against her release has already gathered more than 145,000 signatures, reflecting deep public unease at the idea of leniency for a figure central to one of the darkest chapters in the history of post-war neo-nazism in Germany.

Timeline of the National Socialist Underground (NSU)

1998 Police raids in Jena uncover explosives linked to Uwe Mundlos, Uwe Böhnhardt, and Beate Zschäpe. The trio disappears underground, supported by far-right networks.

2000 Enver Şimşek, a flower seller in Nuremberg, is murdered. He becomes the NSU’s first known victim.

2001–2006 A series of murders target small business owners of Turkish, Kurdish, and Greek background in cities including Hamburg, Munich, Rostock, and Dortmund. Nine men are killed in total.

2004 A nail bomb explodes in Cologne’s Keupstraße, a Turkish neighbourhood. Twenty-two people are injured. Police dismiss racism as a motive, blaming “criminal infighting.”

2007 Policewoman Michèle Kiesewetter is shot dead in Heilbronn. Her colleague is gravely injured. This is the only German victim of the NSU.

2000–2011 The NSU finances itself through at least fourteen armed bank robberies across Germany.

November 2011 Mundlos and Böhnhardt die after a failed bank robbery in Eisenach. Zschäpe sets fire to their flat in Zwickau, destroying evidence. A propaganda video later surfaces in which the group claims responsibility for the murders and bombings.

2013–2018 The Munich trial takes place. Zschäpe is sentenced to life imprisonment, while accomplices such as Ralf Wohlleben are convicted for supplying weapons. Survivors and families remain dissatisfied, citing unanswered questions and institutional failures.

December 2025 Semiya Şimşek, daughter of the NSU’s first victim, confronts Beate Zschäpe in court, condemning the justice system for valuing the perpetrator over the victims. Public outrage grows over Zschäpe’s admission into a deradicalisation programme that could lead to early release.