In a stunning political shift, far-right candidate José Antonio Kast has been elected as Chile’s next president with 58% of the vote in a decisive runoff against left-wing candidate Jeannette Jara.

This election is not just as a change in leadership, but a pivotal choice between two distinct visions for Chile’s future.

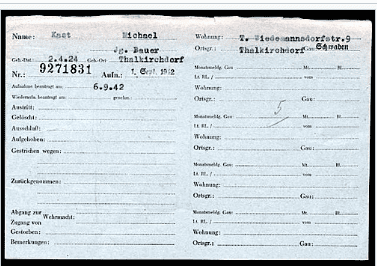

Kast’s personal and political background is closely entwined with some of the most contentious chapters of Chilean and European history. He is the son of German immigrants, and his father, Michael Kast Schindele, was a registered member of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party in 1942.

Kast at first claimed that his father was forcibly conscripted, and only did military service. The publication of his Nazi Party membership card contradicted that claim.

The family’s political prominence in Chile took shape during the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet.

Kast’s older brother, Miguel Kast, was a senior figure in the regime, serving as both a cabinet minister and president of the Central Bank.

Pinochet admirer

José Antonio Kast himself has been an open admirer of Pinochet, once remarking that the dictator “would have voted for me,” a statement that underscored his ideological proximity to the regime.

Kast’s own political career began within the conservative Independent Democratic Union (UDI), a party founded by Jaime Guzmán, one of Pinochet’s closest civilian allies and chief architects of the dictatorship’s institutional legacy.

As a young activist, Kast campaigned for the “Yes” vote in the 1988 plebiscite that sought to extend Pinochet’s rule, aligning himself early on with efforts to preserve the authoritarian order.

A devout Catholic, Kast has taken uncompromising, right-wing positions on social issues, opposing abortion in all circumstances and pledging to roll back Chile’s limited abortion rights. He has also rejected same-sex marriage, framing his views as a defence of traditional values.

Military deployment

On public security, Kast has repeatedly held up El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele as a model, praising his “iron-fist” crackdown on gangs and arguing that Chile needs “more Bukele” to confront rising crime.

He announced plans to deploy the military to high-crime areas and expand the prison system as central pillars of his crime-fighting strategy.

Migration has been another cornerstone of his platform. Kast has vowed to deport hundreds of thousands of undocumented migrants, construct border walls and even a trench along parts of Chile’s frontier, and establish a new police force modelled on the United States’ Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency (ICE).

For many Chilean voters, it seems that current crises carried more weight than historical memory. The election was shaped less by reflections on the country’s past than by anxieties rooted in everyday life, and became a referendum on the present rather than a reckoning with history.

Security concerns

Public concern coalesced around a small number of dominant issues, chief among them security.

Although Chile remains comparatively safe by Latin American standards, a series of high-profile organized crime cases and a sharp rise in homicides between 2018 and 2022 fuelled a widespread sense of insecurity.

By October 2025, this unease was clearly reflected in public opinion, with 63 per cent of respondents in one poll identifying security as their top concern.

Immigration emerged as a closely linked issue. Chile’s foreign-born population has nearly doubled in less than a decade, rising from 4.4 per cent in 2017 to 8.8 per cent in 2024, largely due to arrivals from Venezuela and other countries experiencing acute political and economic crises.

Kast’s campaign capitalised on the pace of this demographic shift, explicitly tying it to perceptions of rising crime and pressure on public services.

Many voters also expressed fatigue with the political establishment and directed their frustration at President Gabriel Boric’s left-wing government.

Softened rhetoric

Learning from his failed 2021 bid, Kast deliberately softened the edges of his 2025 campaign.

He moderated his rhetoric on migration, saying undocumented individuals would be “invited” to leave rather than summarily expelled, and largely avoided discussing his hardline social agenda, focusing almost exclusively on crime and immigration. This allowed him to capture centre-right and disaffected voters.

Generational shift

A generational shift has been central to this change. For younger Chileans who did not experience the 1973 -1990 military dictatorship first hand, the traditional divide between dictatorship and democracy is no longer the primary political fault line.

Their political concerns are shaped more by contemporary issues than by the moral reckonings of the past.

This shift has been accompanied by a softening of public attitudes toward the Pinochet era itself.

Opinion polling suggests a growing ambivalence: a 2023 survey found that 36 per cent of Chileans believed the military was justified in staging the 1973 coup, while 47 per cent described Pinochet’s rule as “partly good, partly bad.”

Revisionism

Alongside this attitudinal change, elements of the right have now moved from ambiguity toward active historical revisionism. Rhetoric that downplays or relativises the dictatorship’s crimes has become more visible.

Recently, for instance, a senior politician from Kast’s party publicly referred to Pinochet as a “statesman” and called for a “more balanced” assessment of his government.

Kast’s presidency, which begins on March 11, 2026, signals significant changes on multiple fronts. Kast has a clear mandate to enact his security and migration agenda. However, with no absolute majority in Congress, negotiating his severe fiscal cuts (including a promised $6 billion reduction in public spending) will be challenging.

Kast’s win solidifies a regional conservative resurgence. He joins a bloc of right-wing leaders, including the hugely unpopular Javier Milei in Argentina and Daniel Noboa in Ecuador, united by promises of security, economic overhaul, and restrictive immigration policies.

Open wound

His victory was celebrated by figures like Milei and Spain’s Santiago Abascal of the Vox party.

The election underscores that Chile’s national trauma remains an open wound. The families of the more than 40,000 victims of execution, torture, and disappearance during the dictatorship are still seeking answers.

Kast’s rise to power demonstrates that a direct political heir to that era can now reach the presidency, not through force, but through the ballot box.