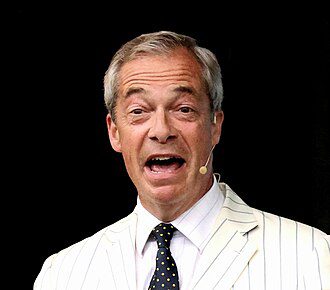

Nigel Farage’s Reform UK stormed into local government in May 2025, winning hundreds of seats across England and seizing control of county councils once thought impregnable.

It was hailed as a political earthquake, a populist breakthrough that would reshape local democracy.

We have already taken a close look at what happened in Kent where, as we wrote, what has unfolded is “a cautionary tale of what happens when incompetent political insurgency meets the everyday reality of public administration”.

Six months on, that picture is replicated in other parts of the country where what began with momentum has unravelled into chaos, scandal, and a collapse of credibility that may threaten the party’s national ambitions. Here are some of the most glaring examples.

Nottinghamshire

In Nottinghamshire, Reform’s largest prize, the party won control of the county council with 41 of 66 seats but quickly descended into paralysis. Committee meetings were cancelled, councillors struggled to grasp basic governance, and officers were forced to intervene publicly to correct false claims.

One cabinet member questioned the validity of climate change data during a flood‑resilience debate, while another was caught on microphone asking colleagues what the council’s statutory duties actually were.

Officers privately described the early weeks as the most chaotic transition they had ever witnessed.

Reform’s attempt to impose a press ban, forbidding journalists from contacting councillors except in “life‑or‑death emergencies,” provoked outrage. Minutes from internal meetings revealed senior figures argued the ban was needed to prevent reporters “setting traps.”

Though eventually lifted, council leader Mick Barton declared he would happily impose one again. Meanwhile, Reform spent £75,000 of taxpayers’ money on Union Jack flags for council properties, even as its “efficiency review” targeted £21 million in cuts to adult social care and £17 million from children’s services.

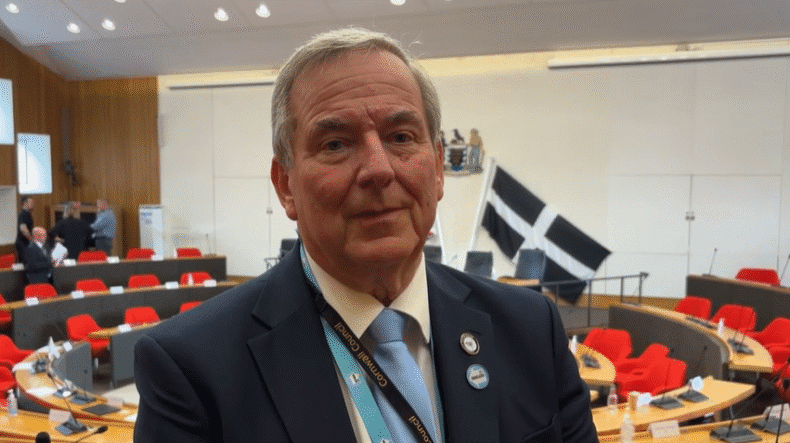

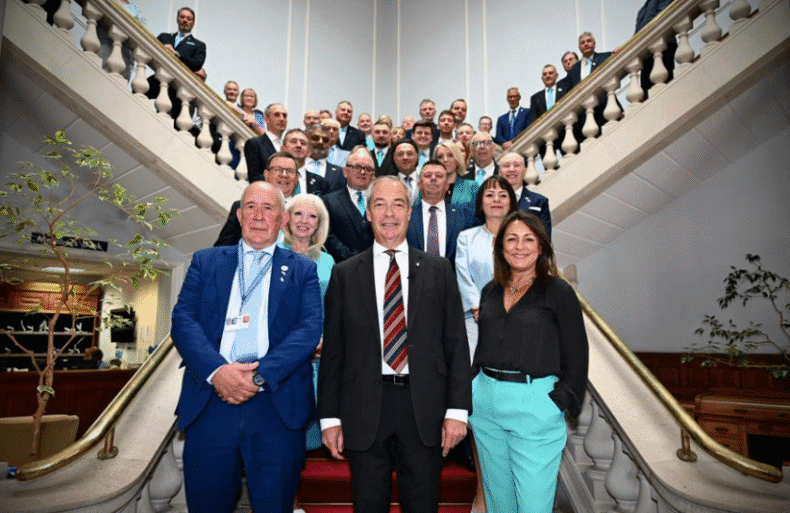

Cornwall

Cornwall saw a different form of collapse. Reform emerged as the largest group with twenty-eight seats but could not assemble a majority.

Within months, both the leader Rob Parsonage and deputy leader Rowland O’Connor resigned, accusing the national party of heavy‑handed interference and of imposing central priorities such as immigration and net‑zero onto local debates about housing and infrastructure where they were irrelevant or unlawful.

Their departure triggered other resignations and defections, leaving Reform with only 21 seats.

Candidates who had expected merely protest roles suddenly found themselves on committees responsible for governing a complex rural county with deep social and economic challenges, and many simply walked away.

Kent

Kent, Reform’s flagship council, as we have already written, became a theatre of dysfunction. A leaked video showed the leader berating colleagues, swearing at dissenters, and demanding loyalty.

Multiple councillors were suspended or expelled, leaving committees understaffed. Reports circulated that scrutiny committees might be scrapped altogether, raising alarms about democratic oversight.

Since we wrote about this in November, two suspended councillors have been expelled.

Seven councillors have now been expelled, one has defected to UKIP, and another faces criminal investigation. Public meetings have grown fractious, with opposition councillors describing the administration as a shambles and accusing Reform of treating the council like a private fiefdom.

Warwickshire

Warwickshire experienced its own upheaval. The newly elected Reform leader resigned after just a month, citing health problems but reportedly overwhelmed by deficits and demoralised staff. His replacement, an 18‑year‑old deputy, became the youngest county council leader in modern history.

Officers were instructed to simplify briefing documents, senior staff worried strategic decisions were being deferred or avoided, and older councillors privately complained the council was being run like a student union.

Derbyshire

In Derbyshire, Reform swept to power with 42 of 64 seats but quickly set about betraying campaign pledges. Five adult‑learning centres were closed without consultation, cutting off 1,300 learners from ESOL, digital skills, and basic education. They also immediately abolished the council’s Climate Change Committee.

And, after campaigning on a platform of cutting costs and reducing council tax, Reform leader Alan Graves admitted that a council tax rise may be necessary next year.

The chief executive’s salary was raised above £200,000, despite promises to end bloated salaries. Community programmes supporting grassroots projects such as village halls, defibrillators, war‑memorial repairs, safety cameras, and local amenities were placed under review.

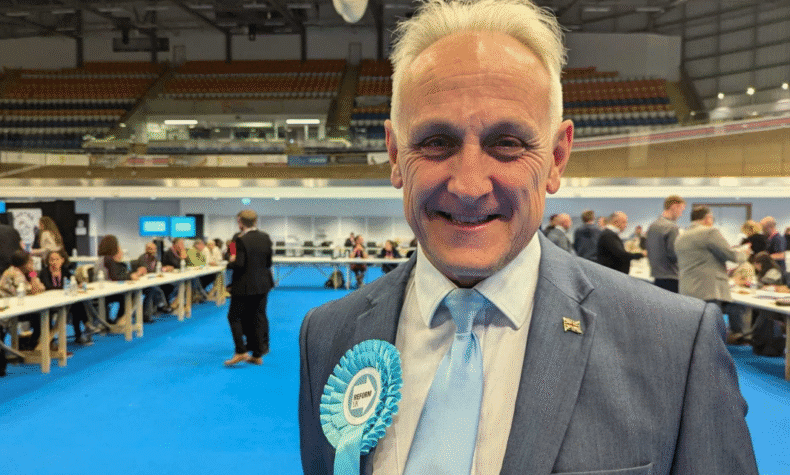

In a snap by-election last week caused by the sudden resignation of councillor Jack Bradley, its cabinet member for Education, Reform held on to its seat, but with 500 fewer votes than in May.

West Northamptonshire

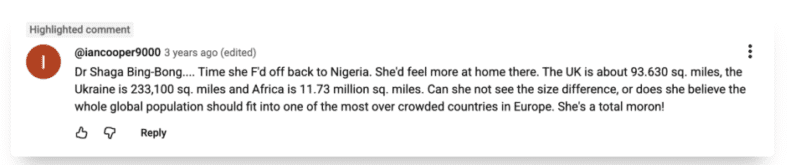

West Northamptonshire has been plagued by scandal surrounding the far-right online contributions of some of its councillors.

First, Councillor Adam Smith was expelled for “concerns about his conduct” and “bringing the party into disrepute.” No further details have been provided.

Then councillor Ivan Dabbs was found to have shared Britain First posts online, but was defended by the council leader despite cross‑party condemnation.

Councillor Ron Firman was discovered to have posted racist and sexist tweets, including remarks about Grenfell survivors being offered residency, and jokes referencing the Ku Klux Klan.

He also mocked Formula One’s decision to scrap grid girls, posting that they should have carried boards saying “my legs are open for refugees.”

Despite widespread outrage, council leader Mark Arnull dismissed concerns and declared his support for both men.

Lancashire

Lancashire saw one of Reform’s largest upsets, with the party jumping from two seats to 53 out of 84. The new administration proposed closing five care homes and five day centres, relocating residents to private facilities.

The move was projected to save £4 million annually but provoked protests from families and residents, condemned as “selling off the family silver.” Conflict of interest allegations arose when the cabinet member for social care was revealed to co‑own a private care firm.

Another councillor, Tom Pickup, was suspended after revelations of participation in MissusKent Jodie Scott’s now notorious WhatsApp group where discussion included stockpiling weapons and targeted killings.

Pickup’s particular contribution was to repeat gross homophobic slurs against Keir Starmer which have featured in one of Jodie Scott’s songs.

Staffordshire

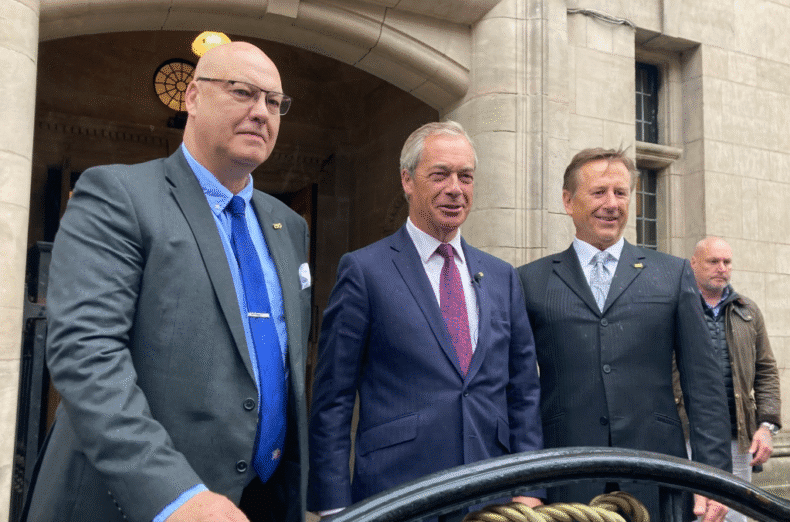

Finally, in Staffordshire, Reform’s council leader Ian Cooper resigned as leader of the County Council after the party revoked his membership over allegations he posted racist comments on social media and that he had failed to declare online media accounts during the candidate vetting process.

His racist posts were first revealed by the ReformExposed account on X and then amplified by further investigation by HOPE not hate.

The local implosions mirror national woes. Nigel Farage himself is under fire for racist insults he made whilst a pupil at Dulwich College and under police investigation over alleged undeclared election expenses in Clacton. Reform denies wrong doing, but it all adds to the sense of instability.

Polling shows the party still leading nationally, but its position slipping. By‑elections have delivered mixed results, with small wins offset by losses. Even symbolic gains, such as Reform’s first (defecting ex-Tory) peer in the House of Lords, have been undermined by defections and resignations.

Across the country, dozens of Reform councillors have quit, been expelled, or suspended. Meetings are cancelled, paper candidates vanish, and councils are left short of experienced hands.

Where Reform has attempted sweeping cost‑cutting, measures have been poorly thought through or reversed under pressure. In other cases, culture‑war rhetoric has trumped local needs, alienating communities and frustrating officers.

The larger question is whether Reform can ever be a governing party. Its rise was fuelled by anger and disruption, but governing demands stability, competence, and compromise.

A warning

Instead, Reform administrations have produced stalemate, infighting, opaque decision‑making, and retreat from democratic scrutiny.

What was promised as a new era is increasingly seen as a warning. Reform’s first experiment in power may be remembered not for transformation, but for exposure: a movement brilliant at harnessing protest, but wholly unprepared for the responsibilities of victory.