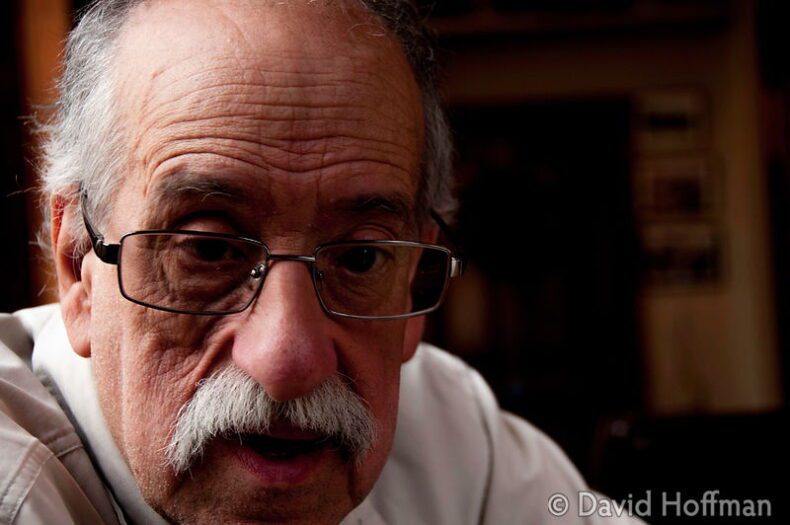

The death of Searchlight’s founder Gerry Gable at the age of 88 marks the passing of a man without whom modern British anti-fascism would scarcely be recognisable. For more than sixty years, he stood at the centre of the struggle against fascism and the extreme right, as a relentless organiser, investigator and strategist.

To many, Gerry was anti-fascism: tireless, uncompromising, occasionally infuriating, and utterly driven by the belief that fascism had to be understood, exposed and defeated before it could take root.

Searchlight was his life’s work. For half a century, until he retired when it moved fully online in 2025, he poured his energy into building it into the most trusted source of information on the far right in Britain.

Intelligence service

It was never simply a magazine. It was an early-warning system, an archive, an anti-fascist intelligence service, and a weapon. Under Gerry’s guidance, Searchlight uncovered networks that preferred to remain hidden, revealed the true nature of organisations that tried to launder their image, and provided countless activists with the knowledge they needed to confront fascism and right-wing extremism locally and nationally.

Gerry understood that public rallies and electoral campaigns were only the surface. The real danger lay beneath: the financing, international links, private meetings, weapons, and violence. Intelligence, he believed, was not an optional extra but the foundation of effective resistance. We were engaged, he would say, in “intelligence-led anti-fascism”.

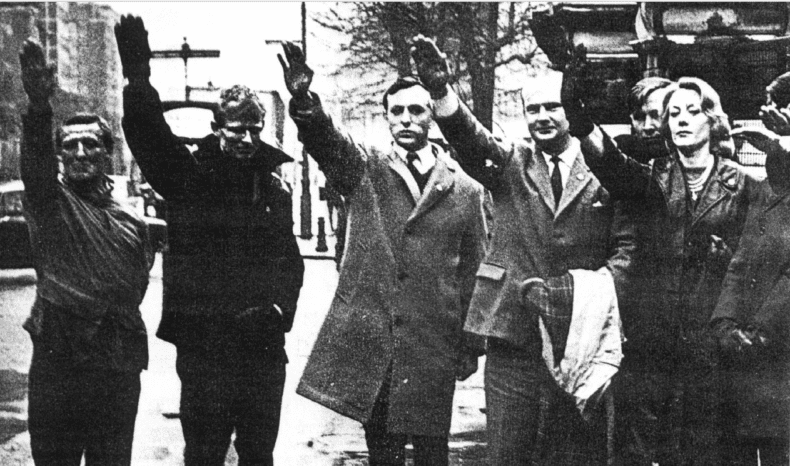

That belief had been forged early. As a young Communist Party activist in the early 1960s, Gerry found himself confronting a resurgent far right that was openly fascist or Nazi in character. Colin Jordan’s National Socialist Movement (NSM) and Oswald Mosley’s Union Movement marched again on British streets, while the authorities often looked the other way.

Traded blows

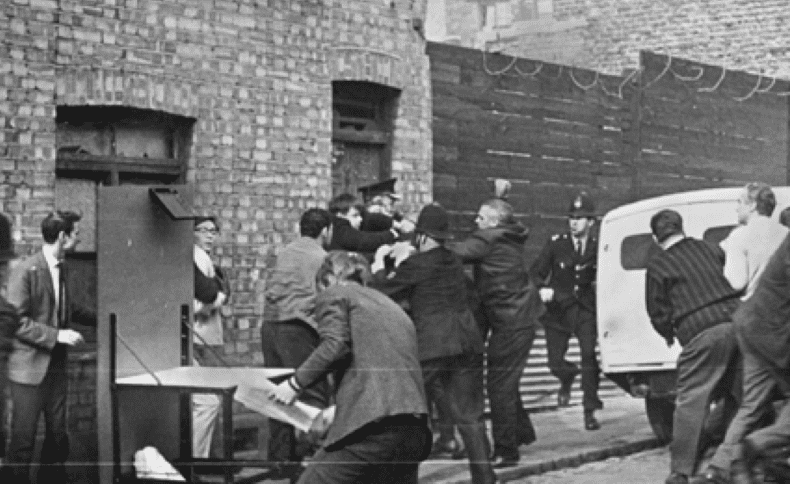

It was at a notorious NSM ‘Free Britain from Jewish Control’ rally in Trafalgar Square in 1962 that Gerry first traded blows with nazis. It was his baptism and set him on a course that would take him through the next six decades. From that moment Gerry helped organise mass opposition, but he also learned that turning out the numbers alone was not enough. Fascism needed to be mapped and penetrated.

This he learned from the semi-clandestine 62 Group, Jewish activists and hardened anti-fascists who were appalled by the reappearance of Nazism so soon after the Holocaust and organised themselves in opposition to it.

Many of these were military veterans of the anti-fascist war, who returned with courage, discipline, a hatred of fascism but, above all, an understanding forged in the most dangerous of circumstances of the vital importance of intelligence to inform successful conflict.

Raids on offices

Although Gerry was never formally a member, he became a trusted collaborator, working particularly closely with the group’s intelligence officer, Harry Bidney. Together, they ran informants, organised the disruption of meetings and carried out daring intelligence-gathering operations, including raids on far-right offices that yielded veritable treasure troves of usable intelligence.

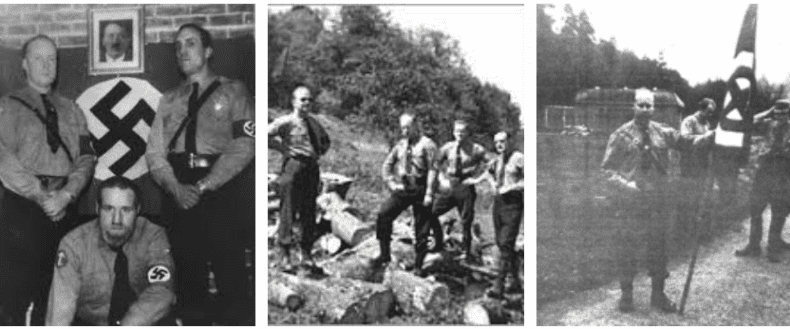

Some of these actions became the stuff of anti-fascist legend: the seizure of membership lists and correspondence in raids on fascist headquarters; the audacious night time burglary of the National Socialist Movement HQ in Notting Hill when it was literally emptied of documents, membership lists, correspondence and photographs; the extraordinary attack on a south London fascist HQ involving a truck driven straight into the building.

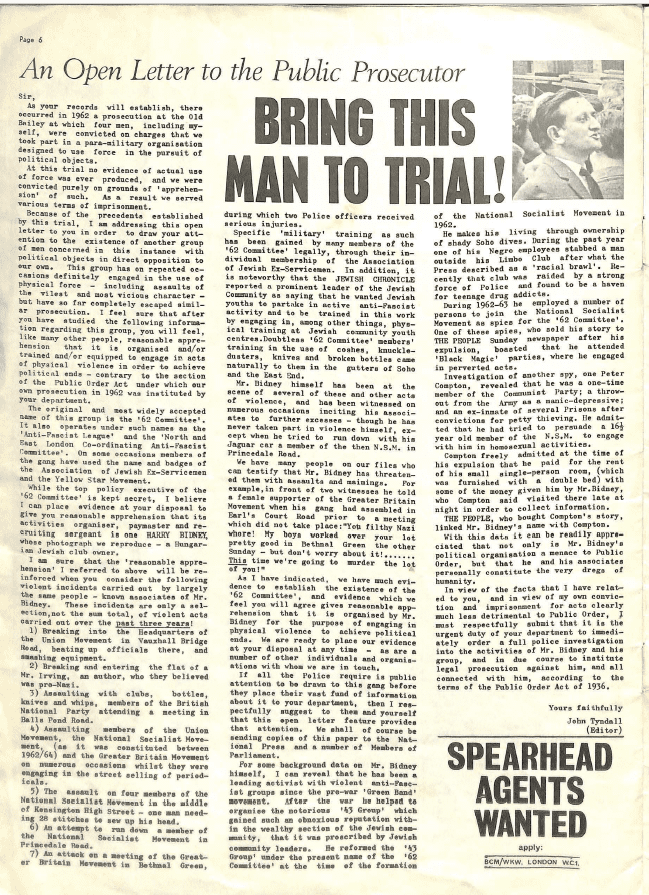

But not everything went smoothly. In 1963, an attempt to obtain sensitive documents from the flat of the then-young far-right ideologue David Irving ended in arrest and conviction. Gerry and two 62 Group members posed as GPO engineers, there to replace the phone cabling, not realising the work had been done only a few weeks earlier. Irving summoned the police.

At trial, however, an apparently sympathetic judge imposed only minor penalties, to Irving’s fury.

Stormed out

Gerry parted company with the Communist Party soon after, when disapproving members of the London leadership began a whispering campaign against him. A heated meeting at party headquarters ended with Gerry storming out, never to return

When a series of antisemitic arson attacks struck London synagogues in 1965, intelligence gathered by Gerry and his comrades proved decisive in bringing the attackers to justice.

At a court hearing involving a number of neo-nazis facing public order charges, Harry Bidney noticed one young man in the dock keeping himself apart from the rest, apparently upset.

The man was approached gently, and poured out his confession – he had been helping make the devices used to set fire to the synagogues. Gerry and Harry persuaded him to turn himself in and give evidence against the rest of the arson gang. Most of those responsible, members of the NSM, were subsequently convicted and jailed.

Francoise Dior, the perfume heiress and Jordan’s wife, who had inspired the arsonists, went on the run to France. She returned secretly to the UK but was arrested after Gerry found her, and confirmed her identity by visiting her safe house pretending to be a sympathiser.

Enduring idea

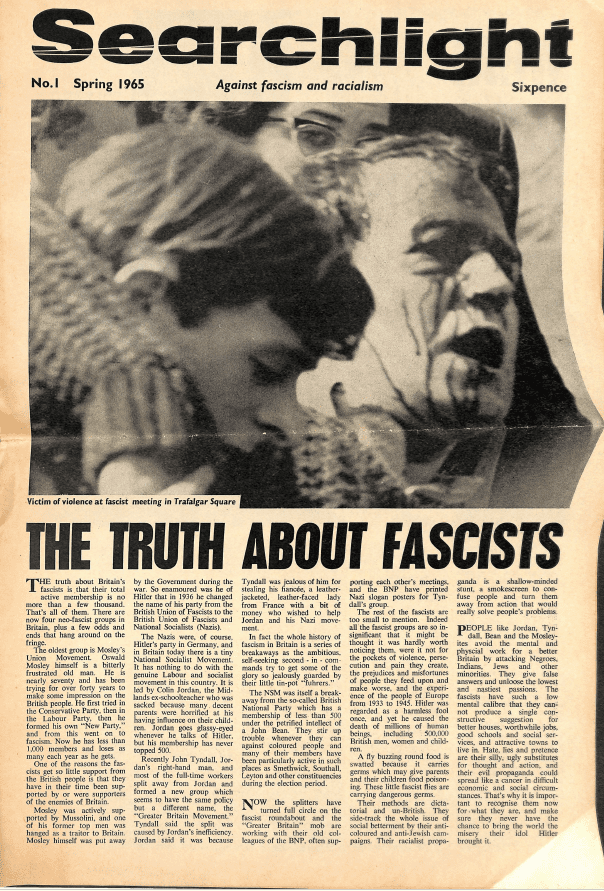

The first incarnation of Searchlight appeared in 1965 as a tabloid newspaper edited by Labour MP Reg Freeson, with Gerry in charge of research. It was the brainchild of the 62 Group and survived only four editions, but the idea endured.

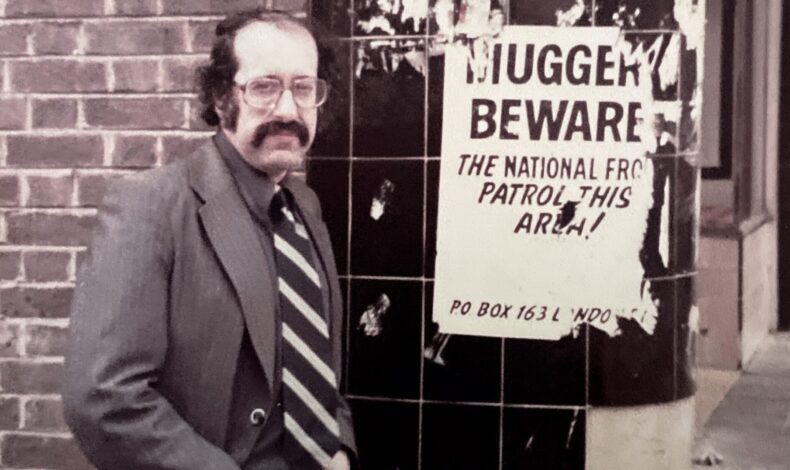

When support for the National Front surged in the 1970s, threatening to normalise fascist politics in Britain, the former leadership of the by-now-defunct 62 Group decided to relaunch Searchlight as a monthly magazine, edited by Gerry and Birmingham-based journalist Maurice Ludmer, a prominent trade unionist and hugely respected anti-racist veteran.

The timing was crucial. Local anti-fascist groups were springing up across the country, hungry for reliable information. Searchlight became their compass. When the Anti-Nazi League was founded in 1977, Gerry and Maurice were among its first sponsors, and Searchlight became its intelligence wing.

Over the next two years the ANL launched a devastatingly successful propaganda blitz against the NF, with the strategic aim of reversing its success by pinning the label ‘nazi’ firmly upon it.

Material provided by Searchlight, especially photographs of NF leadership figures in nazi uniform which had been seized during the Notting Hill raid, played a decisive role.

‘Intelligence-led anti-fascism’ inevitably led to an area of work which became Searchlight’s true hallmark: the use of agents or ‘moles’ within the far-right groups. Some of these were inserted, some had a change of heart and resolved to make amends, some simply wanted money. But you take your informants as you find them. What matters is: have they something to offer and are they acting in good faith?

Stream of intelligence

Over the years, a remarkable stable of incredibly brave men and women provided Searchlight with a constant stream of inside intelligence. Not all of it, for obvious reasons, can be used publicly, but it all goes to inform an understanding of what is going on within the far-right movement and what is driving it.

It was a convert, former Mosley bodyguard Les Wooler, who photographed the entire Union Movement membership records and provided the information which led to on-the-run French fascist assassin Georges Parisy being arrested in London.

It was an infiltrator, Peter Marriner, who exposed a plot by West Midlands British Movement members to stockpile guns and ammunition for ‘the race war’.

It was a reformed nazi, Ray Hill, who brought down British Movement and the British Democratic Party, exposed gun trafficking in Leicester, and prevented a bomb attack on the Notting Hill Carnival in 1981.

It was informants Matthew Collins, Tim Hepple and Darren Wells, all of whom also underwent a change of heart, who allowed Searchlight to expose the activities and plans of the terror group Combat 18.

It was a Searchlight infiltrator, ‘Codename Arthur’ who assisted in identifying the London nail bomber David Copeland.

The list could go on – and indeed it did in the final print issue of the magazine last February where many of these stories were told, some for the first time. And Searchlight still has its agents in place, quietly, day by day, attending meetings and marches, posing as fascist activists, gaining trust, then passing on what they see and hear.

Power of the union

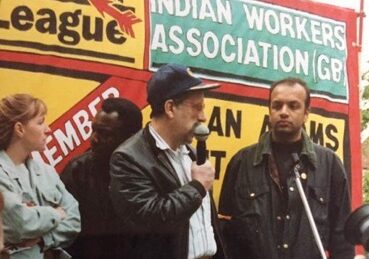

Shaped by its origins in the 62 Group and by a leadership formed in the trade union and communist traditions, Searchlight has carried from the outset a deep, instinctive faith in the power and importance of the trade union movement in confronting the far right.

That conviction was also rooted in Gerry’s own years on building sites in the early 1960s, organising electricians and learning first-hand how solidarity is built and defended. It was a belief that never wavered, and it remains woven into Searchlight’s outlook today, a core principle that will always define it.

Gerry never confined his anti-fascism to the pages of Searchlight. He was endlessly generous with his time and knowledge, whether that meant travelling to speak to a small local group or picking up the phone to offer advice and reassurance. Requests for help were rarely refused.

Learning the craft

Over the years, countless activists in Britain and beyond drew strength from his counsel, and more than one generation of anti-fascists learned their craft under his patient, encouraging guidance.

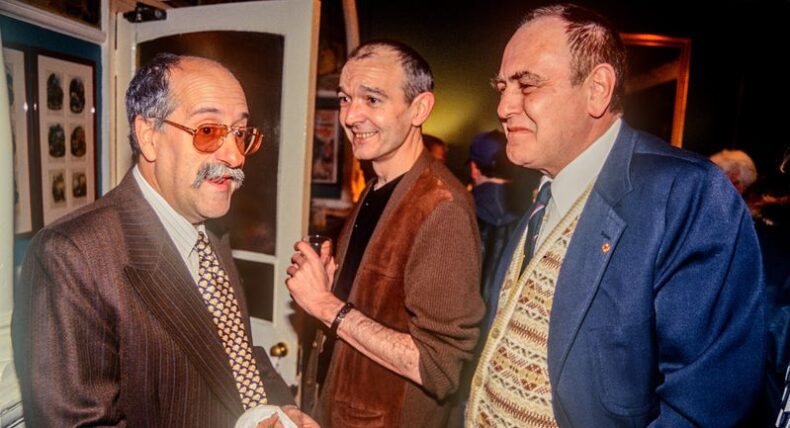

But it has not all been smooth sailing. There was a painful split with HOPE not hate in 2011 which was eventually healed when Gerry publicly offered the hand of friendship to HOPE not hate CEO Nick Lowles at an anti-fascist anniversary event in 2023. “We’ve got enough problems fighting the other lot at the moment, without fighting amongst ourselves” Gerry said at the time.

Enduring tradition

The personal cost of his work was immense. He endured threats, lawsuits, letter bombs and a petrol-bomb attack on his home. That he was targeted so persistently was the clearest measure of his impact, as is the torrent of bile poured online by the fascists since they learned of his death. He would take all of that as a compliment.

And quite rightly; Britain’s extreme right has struggled to gain the footholds it has established elsewhere in Europe, and Gerry’s role in that outcome cannot be overstated. They know it. And that’s why they hate him so, even in death.

Gerry leaves behind not only a publication – now online – but a hugely successful tradition of anti-fascism led and informed by intelligence and analysis, and of vigilance and solidarity that will continue in his absence.

Salud, Gerry. No pasaran!