In early 1975 two antifascist activists published a small magazine. It was 20 pages long, black and white, and most of its content was about the then fast-growing National Front.

There was only one picture, on the front cover: a leather-jacketed young fascist, wearing dark glasses and carrying a union jack, above a familiar antifascist slogan. The original plan wasn’t to produce Searchlight regularly, but only when necessary. It’s proved necessary month after month, year after year, through 496 editions, up to and including this one.

The original plan wasn’t to produce Searchlight regularly, but only when necessary. It’s proved necessary month after month, year after year, through 496 editions, up to and including this one

In 1946, former car mechanic Maurice Ludmer was seconded to the war graves commission, visited Belsen, and dedicated his life to preventing its horrors ever returning. With the Indian Workers’ Association, Maurice set up the Co-ordinating Committee Against Racism, to campaign in Birmingham and beyond.

Like Maurice a Jewish ex-communist, Gerry Gable became the research officer of the 62 Group of militant antifascist activists, created in response to the launch of Colin Jordan’s unambiguously titled National Socialist Movement at a rally in Trafalgar Square (slogan: “Free Britain from Jewish Control”).

National Front’s growing public prominence

Both jailed for paramilitary activities, Jordan and his chief lieutenant John (“Mein Kampf is my doctrine”) Tyndall split, with Tyndall forming the Greater Britain Movement which merged with the fledging National Front (then led by A.K.Chesterton) in 1967. The NF’s growing public prominence culminated in the March 1973 West Bromwich by-election, in which NF candidate Martin (“Why I am a Nazi”) Webster saved his deposit with 16% of the vote. By now Chesterton had been forced out and Tyndall was in command.

In the mid-60s, MP Reg Freeson had edited four editions of Searchlight, a precursor of the magazine Maurice and Gerry were to launch as a permanent feature in 1975. Meanwhile, an early Searchlight infiltrator (“Derek”) used his position in the NSM to conduct a little quiet burglary, amassing documents, membership files and – crucially – photographs. At the end of 1974, Gerry and Maurice published a 16-page pamphlet, its title drawing on a boast by Martin Webster that “we are busy forming a well-oiled Nazi machine in this country”.

Copiously illustrated with NF and other fascist leaders in Nazi uniform, this dossier would prove vital to antifascist propaganda for the rest of the decade

Copiously illustrated with NF and other fascist leaders in Nazi uniform, this dossier would prove vital to antifascist propaganda for the rest of the decade. February 1975 saw the first edition of Searchlight as a regular publication, edited by Gerry, Maurice, and, for a short period, by the antifascist artist Ken Sprague. In August 1975, Searchlight survived a legal attempt by Colin Jordan to close it down.

Like most early Searchlight contributors, I first met Maurice by beating a path to his south Birmingham door. I was researching a play about the National Front called Destiny (later to be produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company and as a BBC Play for Today) and wanted to pick Maurice’s brains. He was looking for contributors, and – as I was thirsty to read contemporary fascist propaganda – he suggested I write a regular ”What Their Papers Say” column, which I did for the following three and a half years.

Act two: electoral successes for the National Front

If the transformation of the openly Nazi NSM/GBM into the pseudo-respectable National Front was the first of the five-act drama of the postwar neofascist right, then Act Two began with some electoral success. In the 1976 locals the NF won 12.3% of the vote in Bradford and 18.5% in Leicester; in 1977 it won nearly 120,000 votes in London, including 19% in Hackney South and Shoreditch. Meanwhile, the breakaway National Party won two council seats in Blackburn.

Although all this was accompanied by threatening marches and violent rhetoric, mainstream opinion needed persuading that British fascism was just that. To this end, Searchlight continued to expose the openly Nazi (and criminal) pasts of the NF leaders, their links to more overt organisations, and – buoyed in confidence by their electoral successes – the Front’s increasingly open espousal of overtly Nazi ideas.

Searchlight continued to expose the openly Nazi (and criminal) pasts of the NF leaders

We translated references in NF literature to “international finance”, “master manipulators” and “cosmopolitans” to “Zionists” and “Jews” (though, by 1976, NF leader John Tyndall didn’t need that much translating). In December 1977, we exposed the fact that leading NF loyalist Richard Verrall had authored a pamphlet (“Did Six Million Really Die?”) which challenged the existence of the holocaust.

And with the foundation of Rock Against Racism in 1976, the physical obstruction of a NF march into multiracial Lewisham in August 1977 and the subsequent foundation of the Anti-Nazi League (with Maurice a founding member), Searchlight’s research and analysis became the content of a mass campaign.

Between 1977 and 1979 the ANL distributed a staggering nine million leaflets, demonstrating to anyone who might doubt it that the National Front was indeed a Nazi Front. In addition, from 1979, the grassroots Campaign Against Racism and Fascism contributed a regular, four-page section to the magazine. There are arguments about the cause of the catastrophic collapse of the NF’s vote at the 1979 General Election (standing 303 candidates, the party gained a paltry 0.6% of the vote).

We have seen the Zionist-red gutter rag Searchlight revealing our own misdeeds issue after issue

National Front memo, June 1970

Margaret Thatcher’s notorious warning about the nation being “rather swamped by people with a different culture” clearly played its part. But in a “private and confidential” NF memo of June 1970, the chief culprit was clear: “we have seen the Zionist-red gutter rag Searchlight revealing our own misdeeds issue after issue”.

Act three: recriminations and splits

If the 1979 general election brought the curtain down on Act Two of the story, Act Three began with recriminations and splits, with fragmented factions often turning to Searchlight to find out what was happening in their own organisations.

In 1982, Tyndall goose-stepped off from the NF to form the no-nonsense-Nazi British National Party, while the movement as a whole turned from electioneering to direct attacks on immigrant populations: the early 80s saw the height of the “paki-bashing” epidemic. While the August 1980 railway station bombing in Bologna – in which 85 people died – inspired a new movement of far-right terror.

For Searchlight, the early 80s were a time of great sadness: having suffered a stroke in February 1980, our editor Maurice Ludmer died of a sudden heart attack on 14 May 1981. Fittingly, Maurice’s last article had been a piece warning against the growing tide of holocaust denial.

He taught antifacism to antiracists and antiracism to antifascists

Searchlight obituary for editor Maurice Ludmer, 1981

In our obituary, we quoted a summation of Maurice’s work which would be repeated, again and again: “He taught antifacism to antiracists and antiracism to antifascists”. It should be added that his commitment to trade unionism was a central plank of the ethos of the magazine, then and now. Maurice’s contribution to Searchlight and the movement it was set up to serve is incalculable.

Those who faced the unenviable task of filling Maurice’s editorial shoes were Vron Ware, Andy Bell, Gerry Gable himself with Sonia Gable, Steve Silver and Nick Lowles. For all of them, a principle task was recruiting, handling and protecting the dozens of informers which the magazine either placed in or recruited from far-right groups.

A strategy of tension

Following Bologna, several Italian fascists wanted by the Italian police fled to Britain, one of them (Roberto Fiore) sharing a flat with the rising NF star (and holocaust denier) Nick Griffin, who, alongside other young NF loyalists, was inspired by the Italian “Third Position” and its advocacy of a “strategy of tension” created by “political soldiers”.

Much of the theory and practice of this movement was discovered and exposed by the unromantic but tried-and-tested device of going through people’s rubbish for notes, letters and lists; a used electronic typewriter ribbon secured a year’s worth of information from then NF Chairman Derek Holland.

But it was also a vital period for moles.

Peter Marriner was one of ours, whose intelligence led to the discovery of a far-right arms cache and the arrest of potential terrorists

In September 1977, Searchlight had “exposed” an alleged far-right infiltrator of the Labour Party; in fact, Peter Marriner was one of ours, whose intelligence led to the discovery of a far-right arms cache and the arrest of potential terrorists.

Other early infiltrators and/or double agents included Les Wooler (Union Movement and Monday Club), and Charles Hanson (NSM); later on came Duncan Robertson (BNP, providing crucial intelligence in Barking and Dagenham), Andy Sykes (effectively dismantling the BNP branch he ran in Bradford, as detailed in the BBC’s 2004 Secret Agent expose), and “Arthur” (keep reading).

Agents within

It’s hard to over-estimate the importance of Ray Hill, who, as deputy leader of the British Movement, managed to bankrupt and collapse that organisation from within, as well as exposing a safe house scheme for exiled Italian terrorists, arms-trading schemes, and a plot by Tony Malksi (of the paramilitary National Socialist Action Party) to bomb the Notting Hill carnival.

Ray’s intelligence formed the basis of a 1981 World in Action documentary on far right gun-running (Guns to the Right) and – after he came out as a Searchlight mole – a Channel Four film and book (co-authored with Andy Bell), both titled The Other Face of Terror.

With Andy Bell now on its staff, World in Action produced no less than three programmes about Combat 18 violence (from 1993 to 1999)

In 1988 Searchlight assisted on another C4 documentary, Disciples of Chaos, revealing the activities of the Political Soldiery (including a Nick Griffin fundraising trip to Libya). In the 1990s, with Andy Bell now on its staff, World in Action produced no less than three programmes about Combat 18 violence (from 1993 to 1999).

Combat 18 had started as the BNP stewarding group in 1992 but quickly turned to violence and terror. In 1997 an internal feud led to the murder of a member of a dissident faction by C18 founder Charlie Sargent (jailed for life in 1998). With over a dozen sources inside the group (including the BNP’s Tim Hepple, the NF’s Matthew Collins and Darren Wells), Searchlight was able to expose C18’s activities, month by month, and destroy its operation.

Meanwhile, the NF’s growing skinhead base were pogoing to Nazi rock groups like Screwdriver, whose leader Ian Stuart Donaldson was to found the “Blood and Honour” network. Effectively shutting down Britain’s Nazi music scene was one of Searchlight’s great achievements in the 1990s.

Effectively shutting down Britain’s Nazi music scene was one of Searchlight’s great achievements in the 1990s

The last terror operation of the 1990s saw David Copeland mounting a nail-bombing campaign in London which left 139 people injured and three dead. Searchlight’s BNP mole “Arthur” was able to identify Copeland as a former BNP member. Act Three – the period in which far-right activities were dominated by violence and terror – had come to a bloody close.

Act four: pivot from violence to electoral success

The next phase of the postwar British far right – arguably, its most successful – had been anticipated in 1993, when the BNP’s Derek Beackon won a seat on Tower Hamlets council, campaigning under the slogan “Rights for Whites”. (In the following three months, racist attacks in the borough rose by 300%).

Beackon lost the seat to Labour eight months later, his victory remaining the BNP’s only 1990s electoral success. In the first decade of the new century, all that was to change.

As Searchlight revealed, the far-right (including Combat 18) contributed significantly to the outbreak of rioting between whites, Asians and the police in the summer of 2001

As Searchlight revealed, the far-right (including Combat 18) contributed significantly to the outbreak of rioting between whites, Asians and the police in Oldham, Burnley and Bradford in the summer of 2001. However, the most important impact of the riots was electoral.

By the end of the 1990s, Nick Griffin had ousted John Tyndall as leader of the BNP and – despite his political soldier past – Griffin determined to pivot the BNP from violence to electoral success.

66 councillors and 14,000 members

The party stood 67 candidates in the 2002 local elections, winning three seats in Burnley. In 2004 the BNP won a further five seats in that borough, as well as seats in Kirklees, Bradford, Rotherham, Pendle, Calderdale, Stoke, Sandwell and Dudley. In 2006 the BNP won 12 of the 13 seats it had contested in Barking and Dagenham and 32 new councillors across the country. In 2009 the party won two seats in the European Parliament. At the height of the wave, the BNP had 66 councillors and 14,000 members.

What happened to that wave was demonstrated by a significant absentee in the BNP’s local government hall of fame: Oldham, where the party never won a seat. This failure was due to a new strategy of community campaigning in areas of far-right strength, led by detailed polling research into why people (predominantly men) were voting BNP.

Hope not Hate

Formally constituted as Searchlight’s campaigning wing in 2004, Hope not Hate had already demonstrated its muscle, during the 2002 Oldham locals, when it exposed the BNP’s leafleting organiser Robert Bennett as a convicted gang rapist and armed robber, a fact spread round the borough by local activists in leaflet after leaflet, to devastating effect.

Buttressed by Searchlight pieces demonstrating low attendance by BNP councillors, as well as inflated expenses and defections, community campaigning gradually turned the tide against the BNP in local government. By June 2008, Nick Griffin was forced to admit that the Hope not Hate operation was so effective that it could beat the BNP almost anywhere.

Two years later, in what could be seen as its finest hour, Hope not Hate took on the BNP both in the 2010 locals and the general election in Barking and Dagenham. Its HQ donated by Unite, the campaign delivered 355,000 pieces of print, made thousands of phone calls, and knocked on tens of thousands of doors.

By the end of election night Griffin had lost his parliamentary race and the BNP every one of its councillors

A particularly effective local election leaflet asked voters if they wanted Nick Griffin teaching their children that the holocaust didn’t happen and Hitler was right. By the end of election night Griffin had lost his parliamentary race and the BNP every one of its councillors. Following Griffin’s humiliating performance on BBC’s Question Time in October 2009, the BNP had been defeated by Hope not Hate activists on the streets and at the ballot box.

Searchlight’s research and intelligence had been central to that victory. The magazine had also been probing into the dubious state of BNP finances. A series of pieces by Sonia Gable told a sorry tale of shredded cheques and invoices, undeclared donations, withheld requisitions to branches and massive increases in staff costs (despite having two MEPs on the lucrative EU Parliamentary payroll).

Nick Griffin defeated

Publicised in a 2008 BBC File on 4 expose, these revelations had the predictable effect of disillusioning and shrinking the membership and drying up donations. Following the loss of his European seat, Nick Griffin was defeated as party leader and subsequently expelled on the magnificently Kafkaesque charge of “trying to cause disunity by deliberately fabricating a state of crisis”.

In 2010, the party had stood 338 candidates; in 2015 it stood eight, its vote share declining by 99.7%. Act Four – during which the far right had achieved its most significant electoral success – was well and truly over.

Act five: fracturing and withering

As in the early 1980s, the collapse of an electoral strategy led the far-right to fracture and return to the streets. Trading under the pseudonym Tommy Robinson, Stephen Yaxley-Lennon founded the English Defence League in June 2009, and, as the BNP withered, the following decade saw a bewildering array of far-right groupings emerging, from National Action (ideology “white jihad”) to Patriotic Alternative (launched by erstwhile BNP militant Mark Collett, star of Channel 4’s 2003 documentary Young, Nazi and Proud), whose many splinters include the Homeland and National Rebirth Parties. Vulnerable to further splits, prosecutions and indeed proscriptions, the far right of the 2010s was appropriately dubbed “post organisational”.

Through the 2010s, Searchlight’s reporters charted the rise of national populism across the European continent and in America

It also faced a new competitor. Through the 2010s, Searchlight’s reporters charted the rise of national populism across the European continent and in America. In addition to UKIP (and its successor Faragist parties, Brexit and Reform), the British national-populist groups included “bridging” organisations between the far right and the Conservatives, like the Traditional Britain Group, whose recent conference attenders included representatives of the Austrian Freedom Party, Germany’s Alternative fur Deutschland, the Patriotic Alternative split-off Homeland, former NF and BNP members and holocaust denier Lady Michele Renouf.

Over the last decade, Searchlight has paid particular attention to the rump UKIP, its increasingly close relationship with “Tommy Robinson”, and its tendency to fracture.

Betraying their own members

Last summer, former UKIP deputy leader Rebecca Jane Sutton decided that Searchlight would be the appropriate vehicle to carry an open letter from her to UKIP members, insisting that “I can’t, in all conscience, sit back and let people keep giving money and trust to UKIP”. Once again, Searchlight revealed how hard right parties betray not only democratic principles but their own party members.

In addition to the dramatic events of the last 50 years, there have been ongoing stories and campaigns which Searchlight has pursued over time. In the 1980s the magazine revealed that former Lithuanian police battalion killer Antonas Gecas was living freely in Scotland.

War Crimes Act in 1991

In October 1987, the magazine launched a campaign to change the law so that war criminals living in the UK could be tried on British soil, which led to the passing of the War Crimes Act in 1991. Gecas died before he could be brought to trial in Britain. However, Antony Sawoniuk was tried for atrocities in Domachevo, Belarus, receiving two life sentences in 1999.

Searchlight provided assistance to the defence in Irving’s failed libel case against Deborah Lipstadt over justified allegations in her book on holocaust denial

Also in pursuit of historical truth, we have regularly exposed historian David Irving’s attempt to whitewash Hitler, first by insisting he didn’t know about the holocaust, and then by claiming it didn’t exist (Searchlight provided assistance to the defence in Irving’s failed libel case against Deborah Lipstadt over justified allegations in her book on holocaust denial).

Exposing nazi infiltration

The magazine has exposed Nazi infiltration of the army and other institutions. And our editor Gerry Gable has been a dogged advocate for the contested but now ever-more demonstrable links between the European far right and Russia.

In its present form, Searchlight was founded 50 years ago in order to serve the antiracist and antifascist movement by providing information in its own columns and the wider media. Much of its intelligence has been provided through the commitment and bravery of informants, many now revealed, many still in place.

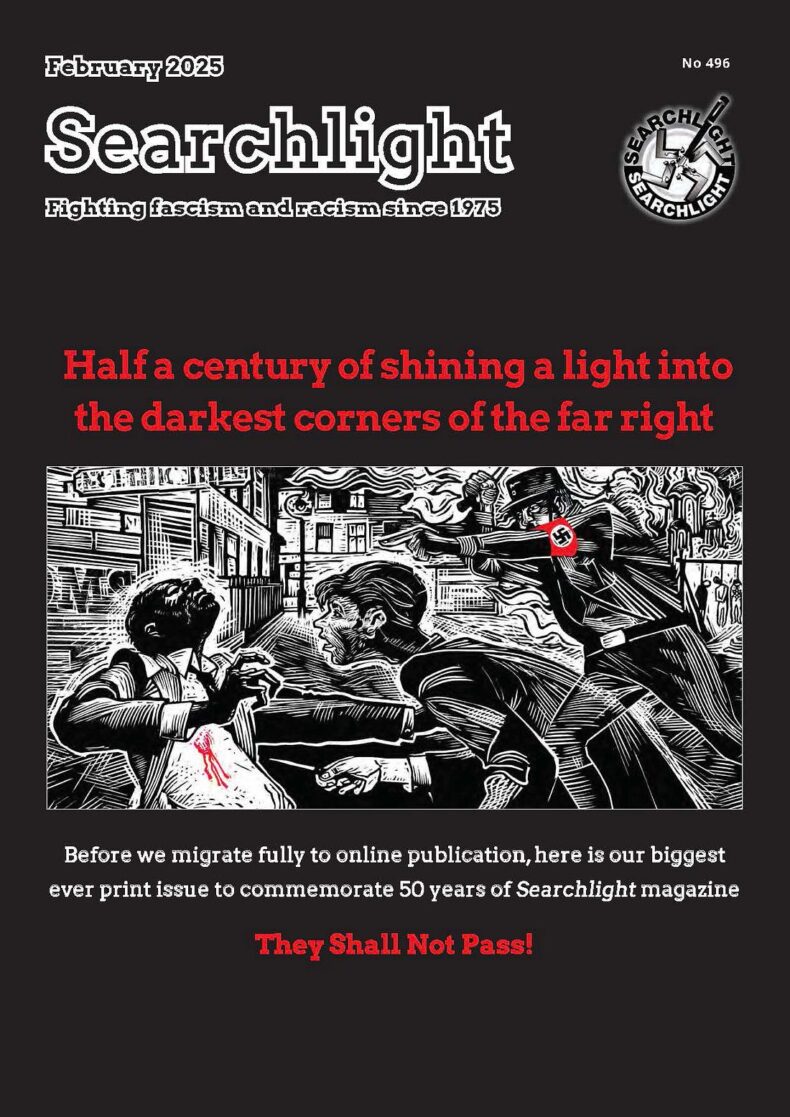

The cover of the magazine’s first 1975 edition bore the 1930s slogan “They Shall Not Pass”. They didn’t pass then, they haven’t passed since, and they won’t pass in the future

No pasarán!

Searchlight will continue to perform that task, for as long as it’s needed, through its online presence and its incomparable Northampton archive. The simple cover of the magazine’s first 1975 edition bore the 1930s slogan “They Shall Not Pass”. They didn’t pass then, they haven’t passed since, and they won’t pass in the future.