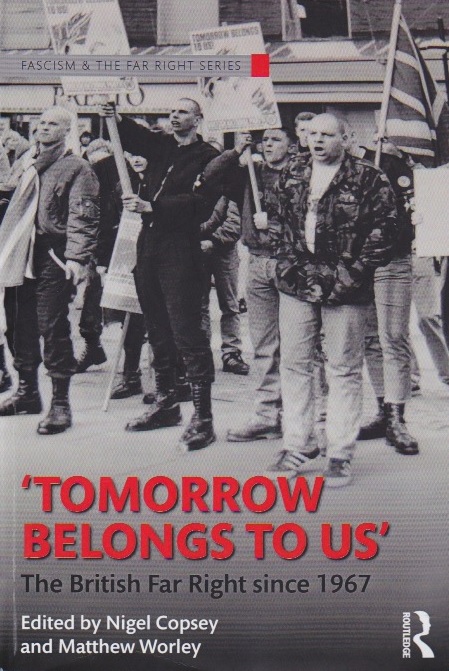

The British Far Right Since 1967

Edited by Nigel Copsey and Matthew Worley

Reviewed for Unite the Union

The starting date was selected because the mergers on Britain’s far right in 1967 created the National Front (NF), the first major fascist party in Britain since the 1930s.

The starting date was selected because the mergers on Britain’s far right in 1967 created the National Front (NF), the first major fascist party in Britain since the 1930s.

Six years later in 1973 the NF candidate Martin Webster at the parliamentary by-election in West Bromwich obtained 16.2 per cent. Following which up until Margaret Thatcher, who adopted some of the language and immigration policies of the NF, was elected as Prime Minister in May 1979 the NF looked set to make a major electoral breakthrough.

The youth wing of the neo-fascist Movimento Sociale Italiano had popularised the anthem ‘Tomorrow belongs to us’ in the 1970s. It struck an emotional chord with fascists globally. The white nationalist British cult band Skrewdriver reworked it in 1984 into a rock anthem that helped construct a successful subculture white power movement with international tentacles.

Then in 2009 the BNP, a party that also won a large number of council seats in the first decade of the new century, had Nick Griffin and Andrew Brons elected to the European Parliament.

These examples are possibly the high points for the far right since 1967.

Consequently ‘tomorrow’ has to date not proven to be the case. Tomorrow though remains and we know from the deathly, barbarous examples of, amongst others, Nazi Germany and fascist Italy in the 30s and 40s that they – the far right – only have to win once for all sorts of groups not to have a tomorrow.

Today we have before us political parties and social movements such as the EDL, the banned National Action Party, the rump of the BNP, the NF and its various offshoots and the British Movement and around which there exists a whole host of subcultures that includes holocaust denial, white power music, racial violence and terrorism.

So what are their beliefs and what is it that motivates the far right organisers and how do they persuade others to join them in developing their authoritarian, rights-free paradise? This book, the sixth and most contemporary in the Routledge study series on fascism and the far right, thus attempts to investigate the politics of the far right so that those who seek to oppose them possess the knowledge of exactly what they are fighting.

There are 12 chapters and they are each concise explanations of the subjects explored.

They include some that are generally ignored when studies of the far right in Britain are conducted such as women’s involvement, homosexuality, music and attempts to develop links across national borders and nationalities.

Some of the more regular subjects covered include holocaust denial and patriotism but not Islamophobia. Whilst it is true that this subject is covered extensively in many other publications I feel this is a mistake because the attempt to build on and generate anti-Muslim prejudice has been the number one agenda item now for far right groups for sometime. There is also an absence of analysis of how far right groups have sought to exploit concerns over unemployment, low pay and zero hours contracts by focusing on the arrival of, particularly since 2004 of EU, migrant workers.

The denial of the holocaust has played a role in many fascist groups but the book points out that it is often hidden from the public if the group concerned begins to attract a reasonable following. Such was the case with the BNP in the 90s and at the beginning of the twentieth century. Once the BNP was though reduced back to a rump in this decade it was willing to, when supporting the openly fascist Greek Golden Dawn party, again express its doubts about the holocaust and how many were massacred by Nazi Germany during it.

Meanwhile attempts to search for a ‘nationalist’ economy have never proven successful with far right groups who whilst being very anti-communist do not wish also to be stridently pro capitalist for fear of repelling working class people, which are the most exploited sections under capitalism.

Attempts at economics usually, at best, come down to a series of bullet points – accompanied by a commitment to stop immigration – such as ban foreign imports, leave the EU and control investment overseas. Where the far right does attack capital it is always aimed at finance or banking capital, with the underlying implication being that these sectors are under the control of Jews and whose influence needs ending.

The two chapters on the Neo-fascist rock music scene of the mid 80s are both of great interest. They show how the far right learnt from the earlier successes of Rock Against Racism to create their own sub-culture. This was for a time highly financially lucrative. It also helped build a rapport and friendship between far right members and supporters from across different parts of Europe. Far right political groups picked up on this to encourage a belief in the defence of white people across Europe as a whole rather than the standard far right belief that ones one nationality is superior to any others even if the skin colours are the same.

The book has an interesting chapter on the importance of patriotism to EDL members and supporters before it ends with an excellent bibliographic survey of Britain’s far right since 1967.

The book is thought provoking and despite my criticisms I would recommend it to everyone who wants to make sure that tomorrow does not EVER belong to the far right.

You can purchase the book at:-