Nigel Farage’s return to the political frontline hasn’t been an altogether smooth ride. Soon after parachuting into Clacton, he was denounced by the sitting Reform UK candidate he had peremptorily displaced. Anthony Mack, now standing against Farage as an Independent, wrote on Facebook: “It’s those sneaky f******s who disguise themselves as good people who do bother me.” No prizes for guessing which “sneaky f****r” he had in mind.

Now the “sneaky f****r” has got himself into difficulties is Northern Ireland. A few weeks before Farage returned to take back the reins of Reform UK from his front man Richard Tice, the party agreed an electoral pact with Traditional Unionist Voice, a hardline right-wing outfit which rejects any compromise with the EU over post-Brexit border questions.

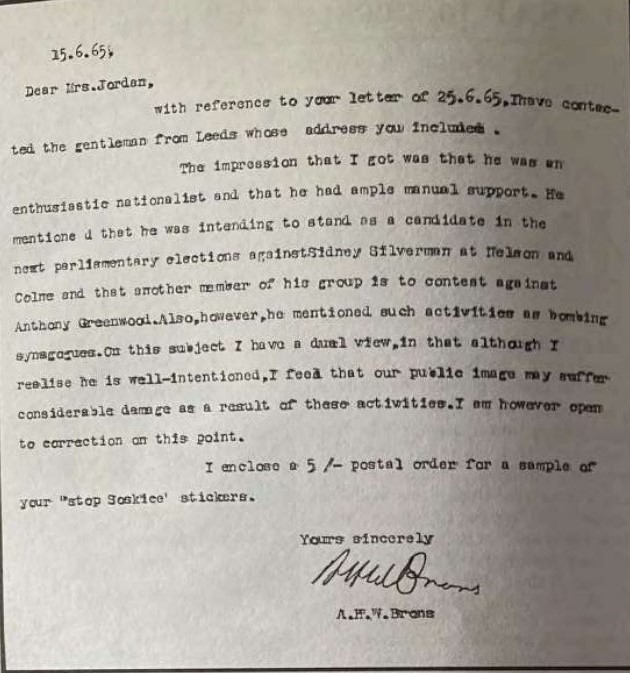

Happier times – Richard Tice signs pact with TUV’s Jim Allister

And as Searchlight has previously exposed, the party includes several former members of the National Front.

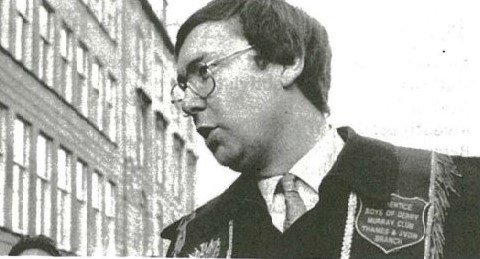

Paul Kingsley is a leading TUV campaigner in Belfast and was election agent for a TUV candidate in last year’s Belfast City Council elections. He spent years in England as a prominent fascist in several parties, first as an NF candidate in Hull, then after a mid-1970s split as editor of British Worker, published by the National Party, and eventually with another breakaway from the NF, the British Democratic Party.

Paul Kingsley

The BDP collapsed after Searchlight mole Ray Hill exposed its gun-running plots. Kingsley went on to work closely with one of Britain’s leading post-war nazis, the civil servant Denis Pirie, but after their schemes collapsed he steadily distanced himself from all of the 1980s NF factions.

Dedicating himself instead to hardline unionism, Kingsley tried to infiltrate the local government union NALGO but his schemes were again exposed by Searchlight.

Another fascist in TUV is John Hiddleston, who first became active with the NF while a student at Queen’s University Belfast. Hiddleston edited the NF’s Northern Ireland journal British Ulsterman

John Hiddleston

After the debacle of the NF’s multiple splits and the failure of NP, BDP and other breakaway parties, Hiddleston emigrated to South Africa. He became involved with several extremist, pro-apartheid movements opposed to any reform of the racist regime.

These included the South African Conservative Party (one of whose MPs was jailed for his involvement in the murder of leading ANC official Chris Hani) and the Herstigte Nasionale Party.

Hiddleston was denounced as a British intelligence informant by rival racists including Alan Harvey, founder of South African Patriot and the Swinton Circle. But he used a range of connections within the Orange Order, and his friendship with well-connected nazis including ex-NF, NP, League of St George, and BNP fixer Steve Brady, to maintain his position in unionism.

After returning from South Africa, Hiddleston was a Northern Ireland Assembly candidate for the Ulster Unionist Party. He then defected to the new TUV, and was a Belfast City Council candidate for them last year.

As Nigel Farage has always been the owner and ultimate controller of Reform UK even before he formally became leader, we can assume he knew about and approved the deal with TUV.

But this week he caused consternation by tearing up the deal and endorsing DUP rather than TUV candidates in two crucial constituencies. One of the candidates Farage is backing, apparently for no other reason that he was a pal of Farage’s during the Brexit referendum campaign, is Ian Paisley, Jr. (son of the DUP’s founder), in North Antrim.

With his typical casual attitude to consistency and integrity, Farage has betrayed not just any TUV candidate, but its leader Jim Allister, who is the candidate standing against Paisley and with whom Reform UK signed a pact just weeks ago.

Farage has already proved that he doesn’t care about associating with racists and apologists for Hitler and Putin. We can assume that his decision to rip up the pact with TUV had nothing to do with the fascists in their ranks.

As with all right-wing populists, Farage portrays himself as a plain-speaking and honest man of the people. In fact, he is a self-centred opportunist with no sense of personal or political loyalty.

Clacton’s voters should be on their guard, and it would be helpful if the Labour Party were to summon up some political courage and speak out against Farage and his gang of extremists and conspiracy theorists.

Forty years ago, the French socialist President François Mitterrand made a historic mistake by cynically boosting Jean-Marie Le Pen’s National Front, so that it would split the conservative vote. We can now see the disastrous long-term consequence of that approach. Perhaps it’s too much to expect decent democrats inside the Conservative Party to reclaim their party from the dog-whistlers, but Labour and Liberal Democrat politicians should take a stand against the far right before it’s too late.