Dr Kat Williams and Dr Siobhan Hyland examine the ascendance of the German far right party in recent elections. Voters in the eastern German states of Thuringia, Saxony, and Brandenburg went to the polls throughout September to cast their ballots in state elections, with the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) finishing first in Thuringia, and […]

Heritage Party leader bemoans ‘injustice’ for holocaust-denying nazi

Searchlight has been reporting for several months on the increasing radicalisation of right-wing parties. Not just the obviously racist and neo-nazi right, but the constellation of parties and groups that are just outside the Conservative Party (and sometimes overlap with the Tory right). The clearest example of this came a fortnight ago when David Kurten […]

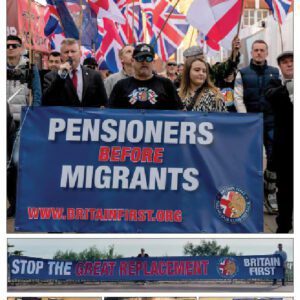

Britain First: The end of the road?

As the party lurches from defeat to disaster, Mark Scholl wonders how much longer its leader, Paul Golding, can continue to kid enough people to fund his futile activities In 2016, Paul Golding and his ex‑girlfriend Jayda Fransen were able to lead several hundred supporters through Rotherham in a protest against so-called grooming gangs. This […]

A shifting kaleidoscope: the state of Britain’s far right at the end of 2024

The current crop of extremist parties and hangers-on follows the same pattern of chopping and changing alliances as in the past. Among this year’s newbies is the Homeland Party, which may – or may not – have prospects. Paul Gale reports This autumn sees Britain’s far-right facing fundamental choices. Searchlight has monitored the usual personal […]

Pssst…Britain First are having a demo. But it’s a SECRET!

This is going to be interesting – BF leader Paul Golding has been boasting about having 20k paid up members. Now he is calling a demo in the Midlands on November 30th. He claims it will be their biggest demo ever. So, it’s put up or shut up time. We will see just how many […]

Is ’two-tier policing’ real? Perhaps – but not in the sense the far right means

On 19 October the far right were granted their post-Southport riots martyr when Peter Lynch died at Moorland Prison. Lynch, aged 61, was just eight weeks into a sentence of two years and eight months for his part in the riot at the Holiday Inn Express in Manvers, Rotherham, on 4 August. The cause of […]

‘Batshit preacher’ to be trumped by Farage?

Nigel Farage has, predictably, been basking in his purported friendship with Donald Trump ever since the disastrous Presidential election result was announced last week. But he’s not the only one. Also posting pictures of himself with the great sex offender is the UK’s far right ‘batshit preacher’, Calvin Robinson, who recently decamped to the US […]

Reform UK’s Plymouth cess pit

Nigel Farage’s Reform UK say they’ve been cleaning up their act since dozens of fascists, racists and other extremists were found in their ranks in the general election, and expelled. But it seems nobody has told them about the party organisation in the southwest. Local anti-fascists in Exeter and Teignbridge have exposed a snake pit […]

Kristallnacht remembered

To mark the anniversary of the 1938 November Pogrom, otherwise known as Kristallnacht, we reprint a special article published by Searchlight in 1988, 50 years after the dreadful events which portended the Holocaust. Never Again.

What Trump’s election means

We are not going to try to list all the ways in which the election of Donald Trump is a catastrophe. That is being comprehensively catalogued in many, many other places and we all know there is much to be feared. Suffice to say that those who believed that the election of Barack Obama in […]

Latest ‘Tommy Robinson’ grift exploits his kids

The Tommy Robinson grift gets more outrageous all the time. Now it’s “with Tommy sentenced to a lengthy prison term, his kids don’t have a dad at all” They have almost exactly as much of a father as they had all the time he was gargling cerveza on the Costa Del Trotter. The Ayia Napa […]

“Splits in Reform UK as senior figures defend Tommy Robinson supporters”

The Guardian reports that there is a split in the leadership of Reform UK, over whether they should support Tommy Robinson (see link below). In fact, this has been brewing. At Robinson’s July ‘Unite the Kingdom’ rally, when they were asked who had voted Reform in the General Election, almost every hand went up. But, […]

Takeaways from today’s ‘Uniting the Kingdom’ rally in London

A few takeaways from today’s ‘Uniting the Kingdom’ rally in London. Without the presence of ‘Tommy Robinson’ himself, the whole thing founders. Numbers attending seem to be not much different from those who attended in July, and were largely, and predictably, middle aged and male. They had to wait for hours, increasingly bored and restless, […]

Tommy Robinson’s key organiser appointed to UKIP executive

Stephen Yaxley-Lennon (aka Tommy Robinson) may not have joined UKIP himself but his right hand-man, and the main organiser of tomorrow’s ‘Uniting The Kingdom’ rally in London, has just been appointed to the UKIP National Executive Committee. The tie-up bteween UKIP and his ‘cultural movement’ which Yaxley-Lennon suggested last week might happen, seems to be […]

Another criminal recruited to UKIP leadership

Never let it be said that UKIP doesn’t offer unique opportunities for speedy advancement. After the election in May of Leader Lois Perry, who had only recently joined the party, and her replacement by Nick Tenconi, a similarly novice recruit, recently announced appointments to the National Executive Committee also boast a sprinkling of brand spanking […]

So why wasn’t Yaxley-Lennon arrested when he returned to UK?

Lots of speculation on Monday about the non-arrest of Tommy Robinson aka Stephen Yaxley-Lennon at Luton Airport when he arrived back in the UK on Sunday night. One press report suggested that the delayed arrest warrant issued against him in August had been triggered. If so, it’s inexplicable that he would not have been detained. […]

Veteran hardline German nazi allowed into the UK for fascist rally

Hiding at a village hall in Staffordshire, Mark Collett’s Patriotic Alternative today confirmed that they intend to abandon any attempt at “mainstreaming” racism. Collett has given up electoral politics and intends instead to follow the extra-parliamentary road previously travelled by Colin Jordan’s British Movement, even though similar strategies have already led to the jailing of […]

Open war breaks out in battle for leadership of British fascism

It’s now a brutal bare-knuckle fight for leadership of British fascism. During the past 48 hours open hostilities have broken out between leading figures from the Homeland Party and Patriotic Alternative, with Homeland’s leader Kenny Smith describing his ex-comrades in PA as “a corrupt and disingenuous fringe cult”. In one corner is Smith (above, left), […]

Violent Australian nazi allowed into UK to speak at rally

A year ago, then Home Secretary Suella Braverman came in for heavy criticism when notorious Spanish neo-nazi Isabel Peralta was allowed in to the UK to address a nazi rally. Now, Labour Home Secretary Yvette Cooper has equally serious questions to answer, as a violent Australian nazi with multiple criminal convictions is allowed into the […]

Sacked Farage spin doctor weaves tangled tale of anti-fascists vetting UKIP members

There’s been a whole lot of outrage on far-right online feeds about a claim made recently by former Reform UK (and Farage) PR man Gawain Towler. He claimed that back in 2010, UKIP, then led by Nigel Farage, asked Hope Not Hate to vet prospective members and candidates who might have extreme far right backgrounds. […]