Former BNP leader says it’s time for ‘direct action’ Mark Scholl considers the implications.

In October 1981 a certain Nicholas John Griffin, then aged 22, stood as the National Front candidate in a by-election for the Croydon North West constituency.

The party had been crushed in the 1979 General Election, because of very well organised opposition in the form of mass movements – principally the Anti-Nazi League – around the UK, and because Conservative leader Margaret Thatcher had spoken of Britain being “swamped” by immigrants.

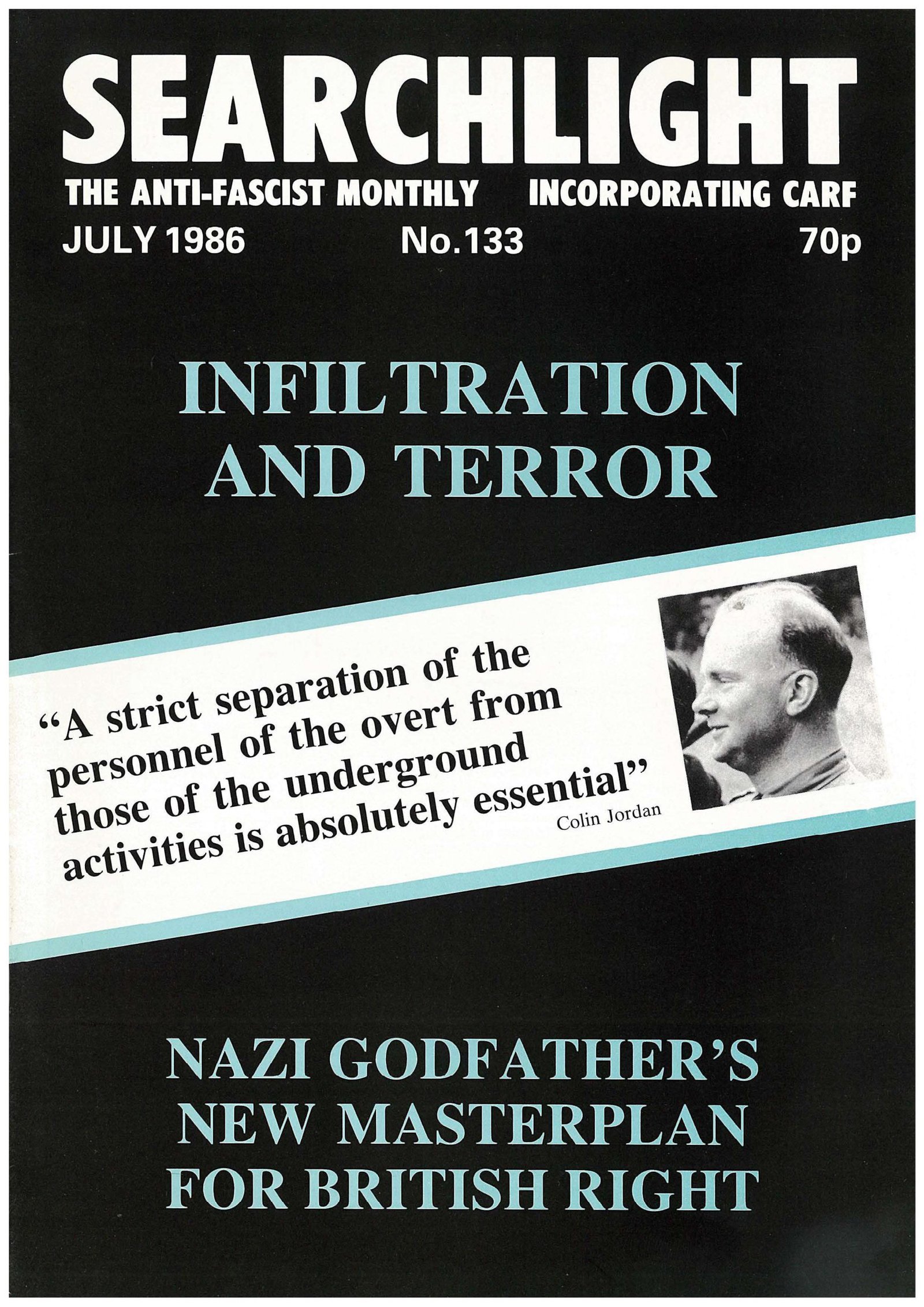

The young Nick Griffin (top) and how Searchlight reported Jordan’s plans at the time (above)

Despite a very active campaign by the Front, and the bussing in of supporters from around the UK to bolster the campaign, the party only managed a derisory 429 votes, or 1.2% of the poll.

Soon after, veteran neo-nazi leader Colin Jordan, now exiled to his bunker at Greenhow Hill by Pateley Bridge in North Yorkshire, wrote a stinging article in the League of St George Journal entitled “Party Time Is Over.” Long convinced that electoral politics was doomed as a strategy, Jordan pointed out the obvious likelihood that a racial Nationalist political party would never do well enough at the ballot box to have a significant impact. He believed in an extra parliamentary strategy of tension, formulated against his background of a long time, and vicious, anti-Jewish politics.

He wrote, “The total content of the television box today decides the total result of the ballot box tomorrow. The party game is thus firmly under the power of the enemy of national and racial resurgence, and indulgence in it by those excluded from television, along with the rest of the mass media, is a waste of time. Even Hitler- who came to power just before his opponents gained this weapon – could not today succeed against and without the magic box.”

“The very raison d’etre of a political party is to appeal sufficiently to the masses so as to obtain sufficient votes in elections as to attain state power, and thus to form a government of the country. Nationalist parties have been operating for decades to this end, and yet have failed to obtain or even come near to obtaining a single seat in Parliament, let alone a necessary majority in Parliament, meaning hundreds of seats. While during those decades the plight of our race and nation has worsened and worsened, such parties have come no nearer success,” he added.

Fast forward to February 2024 and the great wheel of history and events has turned to the extent that Nicholas John Griffin has come full circle and produced a video that comes to the very same conclusions as Jordan did all those years ago. Griffin has, it’s true, been moving in this direction for some time, as Searchlight readers will know, but he’s now firmly nailed his colours to the extra parliamentary mast. Of course, in Griffin’s case, one never knows. In the mid-1980s, partly in response to Jordan’s article, his Third Way ideas pushed the Official National Front, the faction that included himself, Patrick Harrington, Derek Holland and Phil Andrews, towards notions of racial separation, supporting Black supremacists as well as white, experimenting with an extreme Roman Catholic “spirituality” and the creation of alternative communities. All of this ended in failure and farce but, along the way many hundreds of people were conned into giving tens of thousands to Griffin’s self-proclaimed Vanguard Elite.

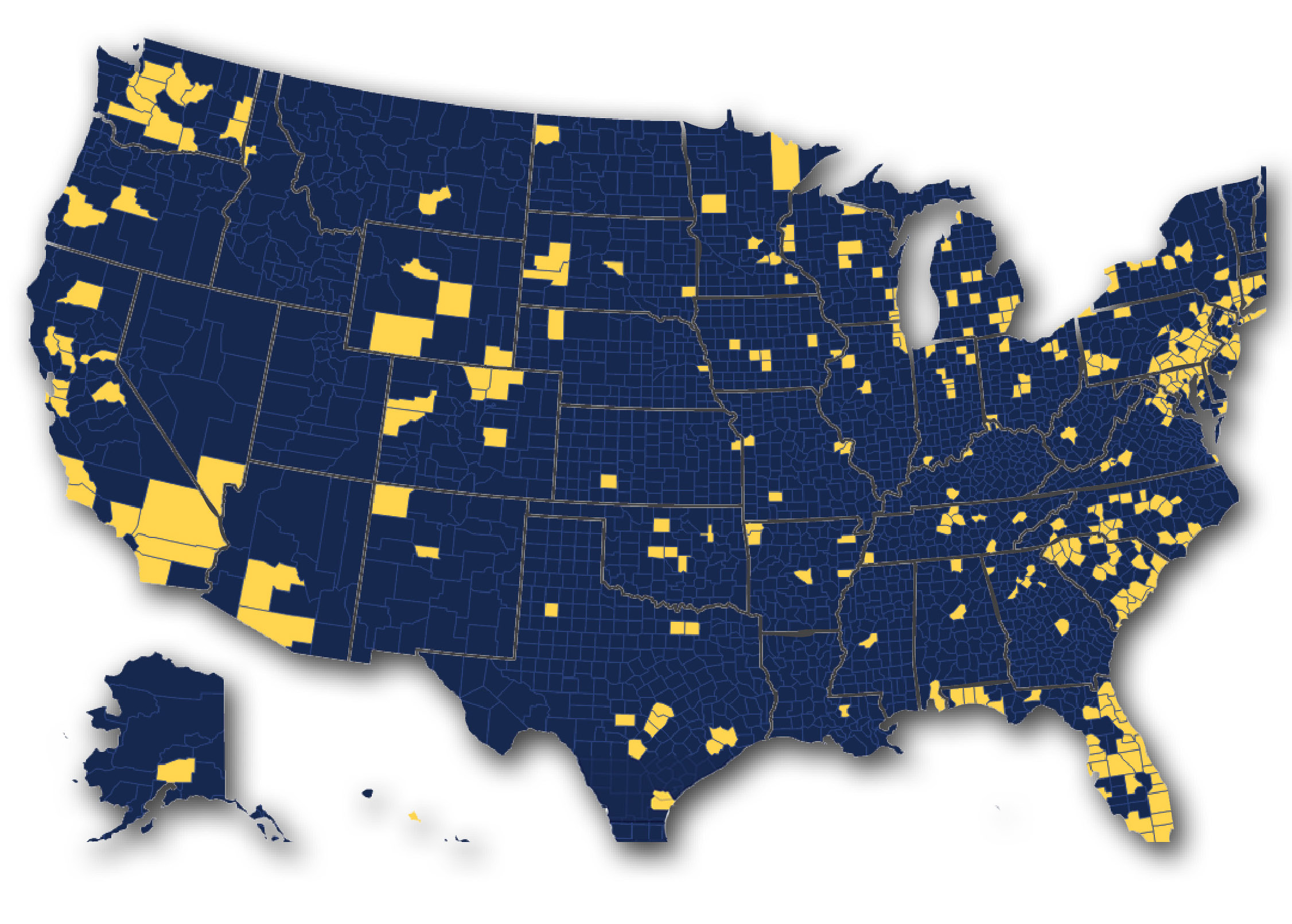

Later on, in the late 1990s, Griffin became a fan of elections. As we now know, much of this had to do with what was good for Griffin, rather than “the British people.” Nevertheless, Griffin’s musings are still taken seriously by many far right extremists because he did, by their lights, manage to succeed, to an extent, by doing well in the very same by-election campaigns he now derides, and because he and Andrew Brons managed to get elected to the European Parliament. But, at its height, the BNP attracted a million votes. A million too many, but this is arguably the maximum number of people prepared to vote for a neo-fascist party in the UK.

This is why Griffin, and his fellow travellers, are angry. They believe they’ve reached the limit of acceptable politics. However, the focus of their anger has not changed. Apart from having to see all those foreign cultures on “their streets,” and having to cope with accelerated changes in terms of economy and society, the far right feels powerless.

The focus for much of this is the Reform Party, that received 13% in the recent Wellingborough by election. Britain First got a derisory 477 votes, less than 2%. It’s Croydon North West all over again. Griffin and co know that Reform, or Reclaim, is always going to soak up the protest vote. It will always get more media attention than outright fascists.

In the past, they were derailed by the anti-immigrant, patriotic rhetoric of Margaret Thatcher. Then, from 2009 onwards, they were outmanoeuvred by her political children in the form of Nigel Farage and friends. Today, Britain’s fascists know they can never hope to win elections when there are well-funded, professionally organised, ultra-right offerings like Reform UK. A “system safety valve” (that’s what every fascist calls political parties and movements not run by violent white supremacists), Reform UK will get the votes they’re chasing, take the money they feel they’re entitled to for being “militant, patriotic, loyal and true,” and be “bigged-up the mainstream media.” On the far-right fringes there’s always a conspiracy theory to explain their permanent failure.

What all this amounts to is a fissure in the far right. On the one hand we have a variety of minor political parties that will fight elections; Britain First, Heritage, British Democrats, National Housing Party, UKIP. The majority of these parties are ex BNP, though a small minority came via the Farage/UKIP route. Elections will be fought not because they’re going to win, but because, they believe, it will raise their profile, gain new members and supporters, and, crucially, bring in additional funds. With this in mind, at least one of these, Britain First, is run as a marketing and merchandising effort; Nick Griffin is envious of the hundreds of thousands that con man Paul Golding has been able to siphon away from his owned warped brand of “effective politics.” But Golding learned from Griffin and his colleague Jim Dowson. The karmic wheel turns…

This split is reflected in the Colin Jordan article. Many dyed-in-the-wool neo-nazis who clicked their heels in the various tiny National Socialist groups of the 1960s (primary amongst them, John Tyndall, Martin Webster and Andrew Brons, not to mention a host of minor activists and local organisers within the National Front in the 1970s) understood that a more nuanced public approach might be necessary. Swastikas and jackboots, as used by Jordan’s National Socialist Movement, were never going to be acceptable to a population that had fought the nazis not many years previously. Hence the National Front, the use of the Union Flag (“it’s our swastika,” said many a neo-nazi within the Front and the pre-Griffin BNP), slightly more restrained language and attempts to keep violent skinhead groups and racist street gangs at arm’s length. Electioneering was seen as a genuine and effective tactic to recruit people for the “coming race war.” In some circles, people recruited out of a concern about immigration, natural small ‘c’ conservatives, would, after a period of education and immersion, become active neo-fascists. Ray Hill was the classic example.

On the other side, at that time, very unpleasant, violent, and often psychotic, groups like Column 88, The League of St George, National Worker’s Party, November 9th Society and British Movement, believed in extra parliamentary activity, from secret meetings (that Searchlight operatives regularly attended) to outright terrorism.

So what has changed?

Not much. The main difference is that the violently psychotic ideas of the extra parliamentary far right are now more dangerous than ever as they’re easy to transmit via social media and online. Nick Griffin’s council of despair could have serious repercussions. He is not the only one. But he’s the one saying it now, loudly and publicly, Activists who are much more dedicated, more violent and even more extreme than him will have come to similar conclusions. His words will give the green light to the more dangerous types on the fringes of the movement. And this has consequences for all of us. We live in a multiracial, diverse society where all are free to pursue their beliefs. The far right seek to undo this. The cynical ones, like Griffin, know that this cannot happen on a large scale, but they still cling to the belief that some sort of dystopian “Max Max” type society might allow their ideas to flourish within a limited geographical sense.

We’ve already seen the violent debacle of National Action, one of the groups that arose from the failure of Griffin’s BNP. It started with talk about keeping fit, holding outdoors events including camping and cookouts, and it ended with violent attacks on mainstream politicians, attempts to threaten, intimidate, or, even worse, bomb. It created an atmosphere of increased paranoia and panic and drove people into the arms of political psychopaths whose end times mindset could only lead to death and destruction.

Today, in the UK, we have British Movement, an openly neo-nazi group run by some of the most unpleasant specimens to be found. It has a history of extreme violence, racial attacks, robbery, criminality and terrorism. In addition to the BM we have Patriotic Alternative, led by neo-fascists Mark Collett and Laura Towler. One of their leaders, Sam Melia, was a member of National Action and has just been convicted of producing racially inflammatory material whose aim is to encourage racial violence.

None of these individuals have an interest in elections and although they claim to be interested in “building white community” we know that this can only go one way; violence. The more “elite” far-right activists believe themselves to be, the more violent they are likely to become. And more self-destructive too.

Searchlight keeps a very close eye on far-right social media accounts, and there are dozens of them. These are a simple and effective way to communicate and attract people into the neo-fascist ranks who would never have given this sort of extremism a second thought in years gone by. (It’s not until you’re in deep that you realise how dangerous and destructive ideas of racial supremacy, societal collapse and the need for “urgent and decisive action.”) Once you’re in the echo chamber it’s not easy to extricate yourself; everything you see and hear colours your attitude to life.

If you add anti-vaxx conspiracy theories into the mix, with a goodly amount of Alex Jones or David Icke style material included, you produce a particularly dangerous brew. You can only keep falling down into the rabbit hole. You realise that it has no ending. It’s very hard to get out.

And it’s all negative. Apart from the ridiculous idea that one can dress up as modern-day Knights Templars, like Griffin and Dowson, and somehow develop a “European spiritual renewal” (based on supporters giving lots of their hard earned money to the cause), or remove litter from local parks as part of a community action plan, what is left for the increasingly paranoid neo-fascist who yearns for action? Leafletting? The occasional picket? A march?

No, what is left is violence which may lead to racist attacks on minorities, and/or attacks on people from the LGBTQ community. We will likely see attacks on properties and facilities housing asylum seekers. This has happened already in Liverpool. This is what Griffin means by extra-parliamentary. This is what he means when he says that party time is ended. It is his 21st Century Strategy of Tension. And you don’t need too many people to engage in this as recent Italian history has shown. Indeed, one of Griffin’s political mentors, and personal friends, Roberto Fiore was the bag man for violent Italian groups that committed numerous outrages in Italy in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Across Europe such violence, based on a rejection of the whole political and social system, by a significant number of people, especially among disenfranchised, poorly educated young men, is on the increase from firebomb attacks on migrant hostels in Germany to shootings in Italy and France.

We live in challenging times. Society is ever changing, too fast for some, and against this background we have a mainstream media fixated by upping the ante where asylum seekers, genuine refugees and “wokeism” are concerned. This is meat and drink to political extremists. They feel it validates their beliefs, and, more importantly, their actions. And when there is “no parliamentary road” the likely result will be violence, whether in mob form via EDL-style street gangs, or as more organised, targeted violence – terrorism.

This is why it is vital that we keep the extra parliamentary far right under ever closer focus. And we at Searchlight are doing this around the clock…