Former leading lights in Vox Macarena Olona, pictured above right with party General Secretary Ignacio Garriga, and Iván Espinosa de los Monteros (left)

Before the parliamentary elections in July many people in the Spain feared a right-wing victory, and the formation of a coalition government between the main conservative party, Partido Popular (PP), and the far-right party Vox.

In the event, the PP gained the highest share of the vote, rising from 5 million in 2019 to 8 million. But Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE), current Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s Labour-type Socialist Party, came an unexpectedly close second with 7.8 million votes, up from 6.8 million last time.

One of the big losers was Vox, which lost more than 600,000 votes, dropping to just over 3 million; in terms of seats gained, it lost out even more, dropping from 52 to 33 MPs.

To the left of the PSOE, there is Sumar, a new coalition led by Yolanda Díaz, the current Employment Minister and Vice-President. It was meant to be a bigger and broader replacement of Podemos, but Sumar actually lost votes and MPs compared with the Podemos-led alliance in 2019.

The overall result in these latest elections made it almost impossible for the right to form a government. This was a great relief. The elections were originally due in autumn 2023, but the then Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez brought them forward following a surge in the municipal and regional elections of 28 May by the right and far right.

With the PP and Vox gaining control of many administrations in many regional governments and local councils women’s and LGBT+ rights have come under attack, as have programmes of historical memory that aim to gain justice for the loved ones of victims of Franco’s dictatorship, whose bodies remain in unmarked graves across the country. They are also pushing against the recognition of (official) languages other than Castilian (Spanish).

In one Valencian town, the newly formed council tried to ban children’s magazines published in Catalan from the local library, but was forced to back down after protests. In another town, the film Lightyear (a spin-off from Toy Story) was banned because it featured a fleeting same-sex kiss between two women.

Vox today

The election setback for the far right contrasts widely with the growth of the right across Europe and has been heralded as a sign that ‘Spain is different’, with Guardian headlines such as ‘Spain bucks European trend of shift towards far right’.

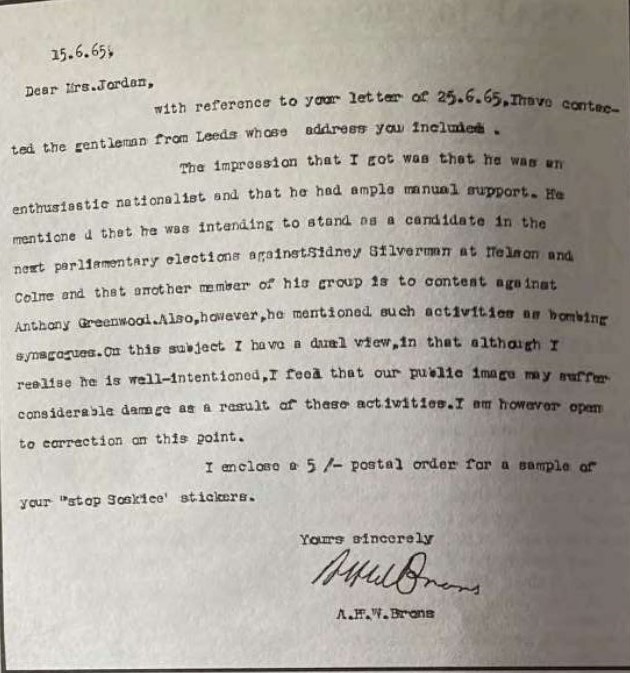

Other good news is that a series of key figures have resigned their positions in Vox, most notably Iván Espinosa de los Monteros. He was a founder member of the party and its main parliamentary spokesperson in the previous legislature. He quit citing personal reasons, but his departure was seen widely as a sign of division between the ultra-liberal, neo-conservative wing — which is losing influence — and the outright fascist wing, which has been gradually taking control of the party, adopting politics based on Catholic fundamentalism and Falangism, the Spanish form of fascism born in the 1930s. An earlier high-profile resignation was that of Macarena Olona, who abandoned Vox in 2022 and spoke of nazi tendencies within the party. Olona was a Vox member in the Congress of Deputies.

However, as often happens with the far right, confusion flourishes.

Some commentators exaggerate the differences between those who have left Vox and those who remain, presenting the former as ‘liberals’. They forget that Espinosa de los Monteros — like Olona before him — was Vox’s spokesperson in Congress when it was promoting brutally racist and sexist positions, going as far as to harass women MPs. Other commentators mistakenly put the party differences down to personal rivalries.

In reality, Vox seems to be following the same pattern as the German far-right party, Alternative for Deutschland (AfD). This initially started out as a right-wing split from mainstream conservatism, but became the new home for increasing numbers of outright fascists and neo-nazis. AfD has seen a long battle between the racist and nationalist conservative hard-right faction and the truly fascist wing led by Björn Höcke. The fascist wing is now in charge, so the AfD is in effect a fascist party (and such organisations operate on top-down control, not bottom-up democracy!).

Vox includes members, even among its leading lights, who simply want a more extremist version of the conservative PP. But, over time, it has attracted individuals who do not simply want slightly more extreme institutional politics, but want to put in questions, from the radical right perspective, the whole system of liberal democracy: that is, fascists.

The strengthening of this faction has contributed to the resignations of party members willing to promote racism, sexism, homophobia, and the attempted elimination of Catalan and Basque national rights etc, but who are interested in neither the rhetoric of a radical break with the current system nor in building a real fascist movement.

The indications are that Vox is closer than ever to becoming a fascist party. The setback it suffered on 23 July may help accelerate the process, with more of those who predominantly want an institutional party returning to the PP, leaving a harder core in charge that is willing to focus on street politics.

New home for extremists

This is especially the case in Catalunya. Here, a decade ago, the former Le Pen-type party Plataforma per Catalunya was the strongest far-right electoral project in the whole of the Spanish state. It almost got into the Catalan parliament in 2010; in 2011, it gained councillors across Catalunya, going as far as to become the second largest party in one city. Thanks to a campaign led by Unity Against Fascism and Racism (UCFR), it was defeated in every election from then on, falling from 67 councillors to just 8 in the 2015 municipal elections.

The party ended up disbanding, with some leading members assimilating into Vox. They may have numbered just 30–40, but these were experienced and committed far-right activists, not simply discontented conservative voters, who rapidly began to take leading positions in the party. They include neo-nazis who have led violent physical attacks on children’s homes sheltering migrant children.

Vox General Secretary Ignacio Garriga, from Catalunya, has made clear his support for far-right thugs involved in street violence, especially targeting Catalan independence supporters. He himself broke off a speech to go and physically confront local people who were heckling an election meeting in July. (Paradoxically, Garriga is black: his mother is from Equatorial Guinea in central Africa, a former Spanish colony.)

In any case, Vox is most certainly a far-right party and, with more than 3 million voters, it is a significant and malignant influence on Spanish politics. But, whatever the exact diagnosis, it is a serious problem.

We must stop them

If one typical reaction to Vox is confusion, the other is passivity. Some newspaper columnists have suggested ignoring Vox, believing that it will just collapse, while others have expressed the view that it is unstoppable. There is little or no serious analysis of what strategies have previously been proven effective in stopping the far right.

This is disappointing, especially given that one such significant example is the defeat of Plataforma per Catalunya in 2015, following a united, focused campaign led by UCFR.

Another key lesson are the series of victories achieved through united struggles against the far right in Britain. These range from the work of the Anti-Nazi League in the 1970s and the defeat of, first, the British National Party and then the English Defence League to, more recently, local protests led by Stand Up To Racism and others against the rump far right in towns across Britain. Another example is KEERFA, the united movement in Greece, whose efforts put the neo-nazis of Golden Dawn behind bars.

These fightbacks show how the broad united struggle against Vox across the Spanish state can be successful – and must be extended.

David Karvala is a founder member and one of the spokespeople of Unity Against Fascism and Racism, the Catalan sister organisation of Stand Up To Racism. He is a co-ordinator of the international network World Against Racism and Fascism and a member of the anti-capitalist group, Marx21.net

This article was first published in the Autumn 2023 issue of Searchlight magazine