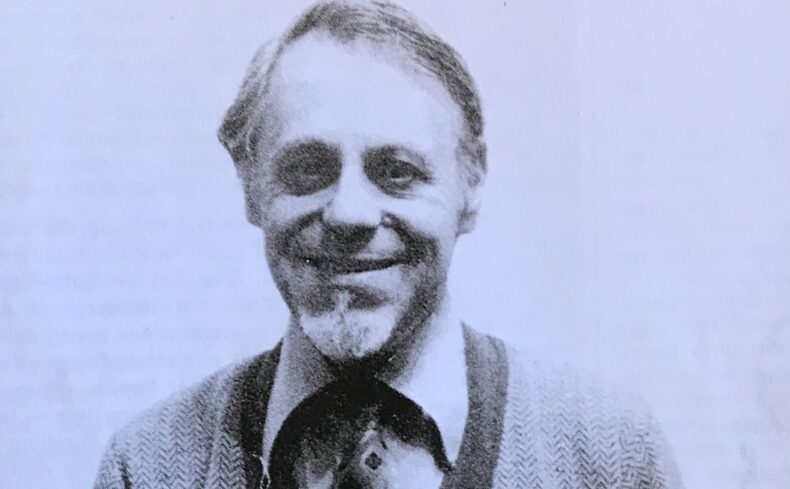

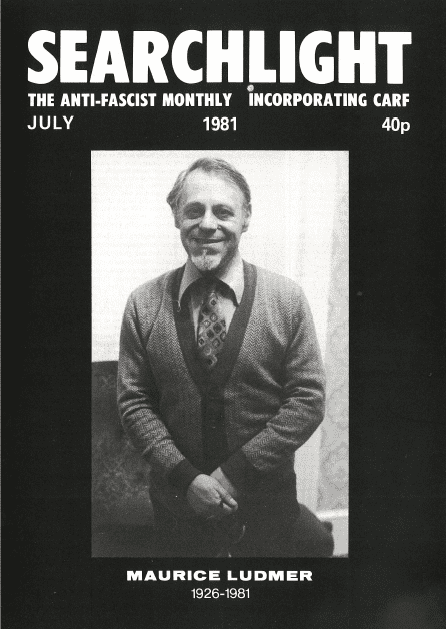

On 14 May,1981, at the age of only 54, Searchlight’s editor Maurice Ludmer died suddenly, depriving the post war anti-fascist and anti-racist movement of one of its leading figures.

Maurice, famously, said “Never again” in 1946 when, as his 1981 Searchlight obituary written by the playwright David Edgar, recounted:

“…a young British Army private, a Birmingham motor-trade apprentice until his call-up, was seconded to the War Graves Commission in Europe, and visited the concentration camp at Belsen.

“It was a year after the liberation, the place had been cleaned up, but there was still enough evidence of the unbelievable atrocities that had happened there, in the heart of Europe, in the middle of the 20th Century.

“And there and then, the soldier pledged himself, wholeheartedly and irrevocably, to seeing that this could never happen again.”

Maurice went into the Army with his political beliefs already well-honed. He was a member of the Young Communist League but the direction in which he was to travel for the rest of his life was set by that visit to Belsen and by the contacts with former members of the French resistance that his work in the Army also occasioned.

When he returned to Birmingham in the early 1950s, and having married his wife Liz, he was at the forefront of campaigning with the Communist Party, active in organisations which it sponsored, like the British Peace Council, and in local tenants and campaign groups.

Deeply embedded racism

But in the ensuing years events were to unfold which would have an enduring effect on his life and work.

First, and particularly in the Midlands where he lived, anti-immigrant racism was spreading like a bush fire, fanned by local Conservative Party associations where racism was so deeply embedded as to be institutionalised.

Notting Hill, in London, and Nottingham were the scenes of violent white race riots and in 1964 a Conservative parliamentary candidate, Peter Griffiths, dumped out Labour’s candidate, the shadow Foreign Secretary Patrick Gordon Walker after Griffiths’ supporters campaigned with the slogan “If you want a n****r for a neighbour, vote Labour”.

Griffiths didn’t use the slogan himself but repeatedly refused to distance himself from activists who did. And then came Enoch Powell, and his “rivers of blood”.

In the vanguard

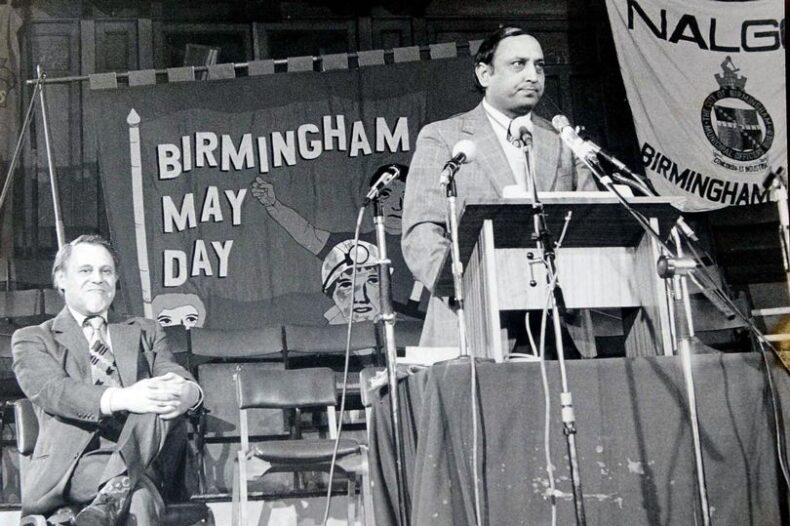

With Jagmohan Joshi and Avtar Jouhl of the Indian Workers’ Association and leaders of other immigrant organisations, Maurice helped set up the Co-Ordinating Committee against Racism (CCARD) which placed itself in the vanguard of confronting the ugly racist tide sweeping through, in particular, white working class communities.

CCARD campaigned on the ground, its leaders often placing themselves at considerable physical risk; it published ground-breaking campaigning materials; and it produced arguably the first clear analysis of how this racism had been spawned and was able to spread.

It was because he felt that it was paying insufficient attention to the issue of white, working class racism that Maurice parted company with the Communist Party at this time.

Fascists gearing up

But something else was going on as well. Various neo-Nazi and fascist groups, who for pretty obvious reasons had gained little traction in the early post-war period, were now gearing up, taking full advantage of the hostility being whipped up against immigrant communities.

In London, where opposition to the likes of the National Socialist Movement and the Greater Britain Movement was focussed, Searchlight magazine was first published. Its editors included two Labour MPs and its research director was Gerry Gable.

In its first iteration, in newspaper format, it appeared only a handful of times but it brought Maurice into contact with those at the sharp end of anti-fascist campaigning and when it was relaunched in 1975, Maurice was first its Managing Editor and, shortly afterwards, Editor with overall editorial control.

Far right resurgance

The relaunch was in direct response to a resurgence of the far right. In 1967 a process of coalescence had begun when the League of Empire Loyalists and the British National Party combined to form the National Front under the leadership of A K Chesterton.

It was joined by the Greater Britain Movement, led by John Tyndall, who in short order deposed Chesterton and took over.

It achieved impressive growth in a short space of time, successfully plundering Conservative Associations all over the country for racist members who brought with them political skills and experience the extreme right had previously lacked.

A significant threat

By the mid-1970s the National Front posed a significant potential threat winning tens of thousands of votes in local elections and turning out sizeable street demonstrations.

It was a turning point. Searchlight was at the forefront of campaigning against them, analysing what was going on and exposing the leaders for what they were – unreconstructed Nazis concealing their true affiliations to ride the racist wave.

Searchlight serviced the network of local anti-fascists and anti-racist groups around the country with intelligence and reported on their activities.

Devastating propaganda

And when most of these local groups were superseded in 1977 by the launch of the Anti-Nazi League, it was fitting that Maurice should be a founder member.

The intelligence and campaigning material provided by Searchlight were absolutely central to the devastating propaganda campaigns subsequently waged by the ANL against the National Front which played such a huge part in that organisation’s demise.

But Maurice was more than just a political animal. He loved sport, a passion which began when he was at college as a young man, and until he died he was the Morning Star’s football correspondent regularly reporting from games around the Midlands.

He was President of Birmingham Trades Council and Branch Chairman of Birmingham NUJ. He loved music, devoured books and films, was a passionate cook and, above all, a family man utterly devoted to his wife and children.

Unique contribution

Maurice’s unique contribution to our struggle was well put by David Edgar in the 1981 Searchlight obituary:

“Maurice believed passionately that fascism could not be effectively fought without attacking racism as well; he believed, too, that black workers must play their full part in the struggle against the most extreme and virulent form of racism, the National Front and its allies.

“Throughout his life Maurice taught anti-fascism to anti-racists and anti-racism to anti-fascists, convincing each of the vital necessity of unity. Perhaps uniquely among anti-racists, he was bitterly aware of the ideological continuum between the mildest racialist sentiments and death camps”.